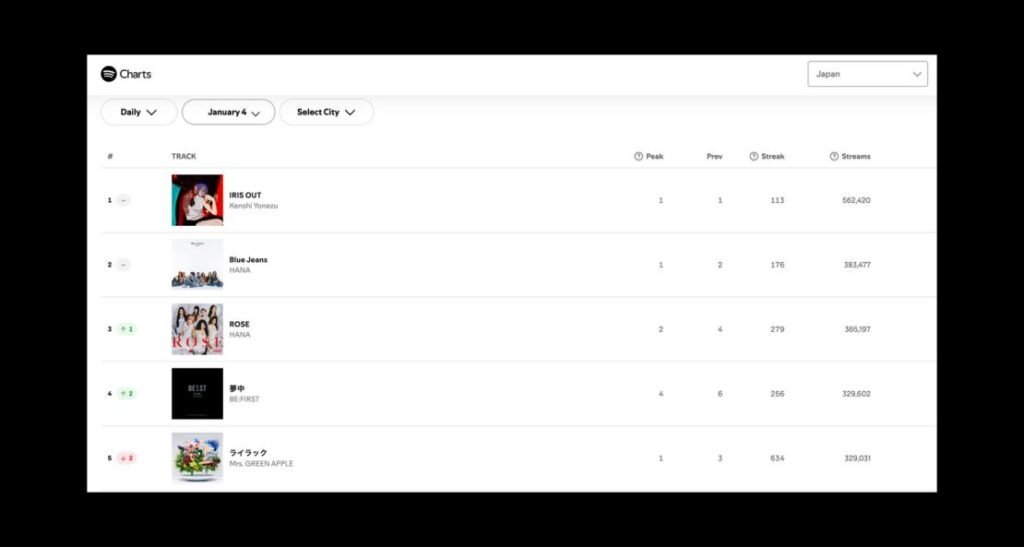

The Japan Spotify chart for 4 January 2026 tells a different story from the UK. Where Britain’s top 10 mixes global pop with rising British acts, Japan’s chart reads like a masterclass in cultural persistence.

Eight of the top 10 positions belong to Japanese artists. The other two? Also Japanese.

This isn’t xenophobia. It’s preference working at scale.

The Kenshi Yonezu Effect

Kenshi Yonezu’s “IRIS OUT” sits at number one. Not remarkable on its own, until you scan the rest of the chart and find Yonezu appearing six more times across the top 200. Position 11: “JANE DOE” with Hikaru Utada.

Position 65: “1991”. Position 68: “KICK BACK”. Position 74: “Lemon”. The pattern repeats.

This is artist loyalty rendered as data. Yonezu doesn’t have one hit; he has an ecosystem. His fans don’t stream a single and move on. They stream the catalogue, treating each new discovery as an entry point to the rest.

The UK chart shows hit-driven behaviour. Japan’s chart shows something older: the album era’s logic, now applied to streaming.

Mrs. GREEN APPLE’s Chart Saturation

Mrs. GREEN APPLE appears 24 times in the top 200. Twenty-four distinct positions.

Position 5: “ライラック”. Position 8: “ダーリン”. Position 13: “Soranji”. The band isn’t gaming anything.

They’ve just released enough music that connects locally to occupy roughly one in eight chart positions through volume alone.

When you have that many songs and all of them work for your audience, this is what the data looks like.

Compare this to the UK, where even massive artists rarely hold more than three or four positions simultaneously.

The Japanese model treats streaming as portfolio listening. The Western model treats it as singles consumption.

The Demon Hunters Anomaly

Position 33: “Golden” by HUNTR/X, EJAE, AUDREY NUNA, REI AMI, and the K-Pop Demon Hunters Cast.

The same fictional soundtrack dominating the UK charts has cracked Japan’s top 40. It’s not at number one (Japanese audiences aren’t surrendering that easily), but the fact it’s here at all matters.

In the UK, “Golden” holds the summit because it arrived in a market where playlist culture dominates and emotional resonance beats artist identity.

In Japan, it enters a chart where Aimyon’s “はロックを かない” has maintained continuous chart presence for 2,880 days (nearly eight years), currently sitting at position 89.

The Demon Hunters soundtrack enters a market where longevity isn’t anomalous; it’s expected. If the music connects, it stays. If it doesn’t, no amount of Netflix promotion can force it.

Worth noting: Spotify remains a limited lens on Japanese music consumption. Japan’s physical music market still accounts for a larger share of revenue than most Western markets, and platforms like YouTube and LINE Music carry different demographic skews.

But what Spotify does reveal is telling. It shows what happens when a global platform enters a market that never fully bought into the singles-driven, playlist-first model that reshaped Western listening.

K-Pop’s Measured Presence

K-pop appears throughout Japan’s chart, but not as conquest. Call it integration instead. BTS members Jimin and Jin hold positions 25 and 26.

ILLIT places three tracks in the top 140. ROSÉ and Bruno Mars’ “APT.” sits at 141.

These aren’t dominant positions. They’re the chart placements of respected guests. Japan streams K-pop the way it streams most things: when it’s good, it charts. When it’s merely popular elsewhere, it gets ignored.

Compare this to how K-pop storms Western charts through coordinated fan action, often debuting high then dropping fast. In Japan, K-pop tracks enter lower and sustain longer.

“Whiplash” by aespa debuts at 111, up 12 positions. “SPAGHETTI” by LE SSERAFIM enters at 83, up 7. Not explosive. Steady.

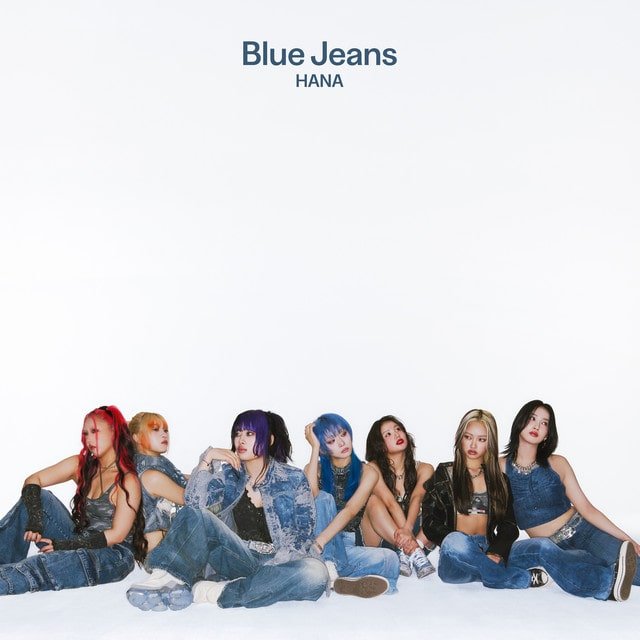

HANA’s Quiet Dominance

Scan the chart and you’ll find HANA appearing 10 times between positions 2 and 180. Ten distinct placements for a girl group most Western listeners have never heard of.

“Blue Jeans” sits at number 2. “ROSE” at 3. “NON STOP” at 10. The positions continue downward, but the pattern holds. HANA isn’t a global phenomenon.

They’re a Japanese success story, operating inside a market that rewards consistency over viral moments.

Their catalogue streams the way Mrs. GREEN APPLE’s does: multiple tracks simultaneously, suggesting fans who return to the full body of work rather than cherry-picking singles.

This is catalogue behaviour at the group level. Not unprecedented, but notable in scale. HANA holds more chart positions than most Western acts manage in their entire careers, and they’re doing it in a single week.

Fujii Kaze’s Understated Presence

Fujii Kaze appears six times across the chart. Not dominating like Yonezu or Mrs. GREEN APPLE, but present enough to signal sustained attention. Position 61: “Kirari”. Position 124: “Michi Teyu Ku (Overflowing)”. Position 128: “Garden”. Position 134: “Tabiji”. Position 137: “Hana”. Position 189: “Prema”. The placements continue.

Kaze represents a different tier of Japanese streaming success. Not at the summit, but consistently charting across multiple releases.

Six positions suggests an artist whose fanbase streams selectively but repeatedly. Quality over quantity, perhaps. Or simply an artist who’s built a following that returns without needing algorithmic prompting.

Worth noting: both HANA and Fujii Kaze demonstrate that Japan’s chart depth extends well beyond the top 10. Success doesn’t require summit positions when your audience streams multiple tracks consistently.

The Back Number Phenomenon

Back number (a Japanese rock band) appears 18 times across the chart. Position 14, 15, 18, 20, and onwards.

That’s nearly one in eleven positions, not through algorithmic manipulation but because Japanese listeners apparently treat the band’s catalogue like a personal rotation playlist.

This is what catalogue streaming looks like when it develops around artist loyalty rather than algorithmic discovery.

Western habits push toward novelty. Japanese habits, at least on this chart, push toward depth.

What the Data Actually Shows

Every music chart measures behaviour shaped by how people encounter music in that market.

The UK chart reflects an ecosystem built on playlists, algorithmic discovery, and cross-cultural accessibility.

Japan’s chart reflects something else: domestic preference, artist loyalty, and catalogue depth still winning out over recommendation engines.

The UK chart shows what happens when music functions as emotional utility first, artist identity second.

Japan’s chart shows the reverse. The Demon Hunters soundtrack crosses both markets because it manages both functions at once.

Kenshi Yonezu, Mrs. GREEN APPLE, and back number combine for over 60 chart positions between them.

The Demon Hunters soundtrack sits at 33. That’s not a barrier breaking. That’s a door opening slightly, on Japanese terms.

Geography Still Shapes What We Hear

UK’s top 10: five nationalities, multiple genres, one fictional soundtrack at number one.

Japan’s top 10: one nationality, consistent genre preference, domestic artists holding ground.

The contrast isn’t about openness versus isolation. It’s about how markets assign value differently.

The question isn’t which approach wins, but whether convergence continues or whether markets like Japan prove that streaming can scale without erasing local taste.

Right now, Kenshi Yonezu sits at number one in Japan while Olivia Dean holds that position in the UK.

Both are domestic acts. Both represent their markets’ preferences. Both prove that even in 2026, geography still shapes what people choose to hear.

The algorithms suggest. The charts show what people actually choose. And in Japan, they’re mostly choosing their own artists, with one animated demon-hunting exception sneaking in at position 33.