You are halfway through the day, and a choice will not leave you alone. Two versions of the same thing, both fine, neither obvious.

You replay scraps of evidence, ask a quick second opinion, and tell yourself you will sleep on it.

That loop is where critical thinking lives, not only in classrooms, but in the everyday shuffle of picking one option over another.

Plain meaning: critical thinking is the habit of testing ideas before you run with them, spotting weak links, checking the support, and staying open to a better answer.

Psychologists define it as problem-focused thinking that checks ideas or possible solutions for errors or drawbacks, see the APA Dictionary of Psychology.

A simple checklist that travels well

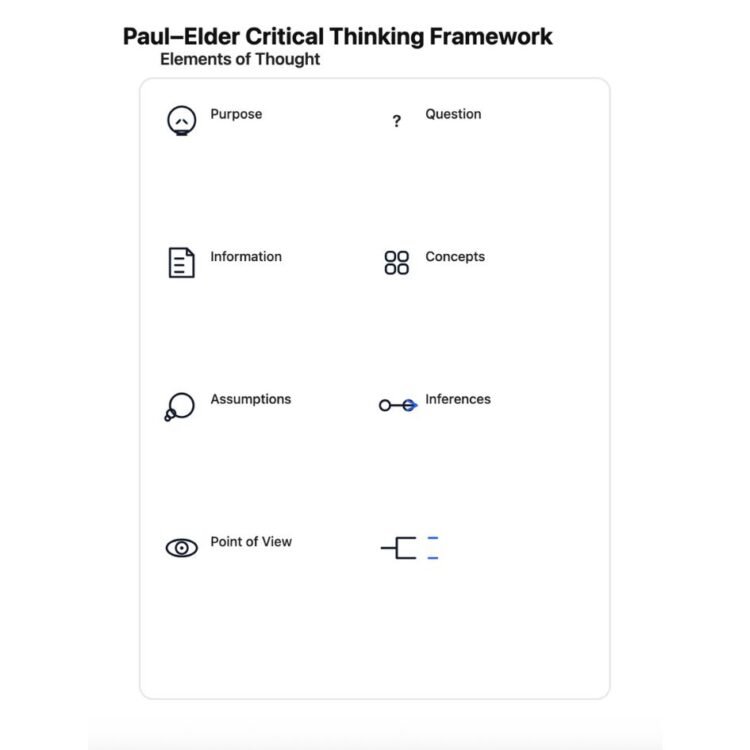

One handy model is the Paul–Elder framework, which asks two things.

What are you working with, for example, purpose, question, information, concepts, assumptions, point of view, and likely results?

How good is your thinking, for example, clarity, accuracy, relevance, depth, breadth, logic, and fairness?

See the University of Louisville overview of the Paul–Elder framework for details.

Walkthrough example:

You think Version B works better.

- Information: three listeners preferred it, and it was louder in the A and B test.

- Assumptions: louder means better, and your listeners were not swayed by mood.

- Standards check: after level-matching, does B still win for accuracy, and have you asked people who do not share your taste for breadth.

The core skills, told through small moments

Experts commonly group critical-thinking skills as interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, explanation, and self-regulation, a set drawn from the Delphi consensus. See Facione’s summary for the list.

- Interpretation means stating what the thing actually shows before judging it.

Example: a graph shows plays dip on weekends, save your theory for later. - Analysis means breaking a claim into reasons and evidence.

Example: “this source is reliable” becomes author name, citations, and publisher policy. - Evaluation means asking whether the evidence really fits the claim.

Example: a chart with no source lowers your confidence. - Inference means drawing a conclusion and saying how sure you are.

Example: “B looks stronger at about 70 percent confidence from 200 responses.” - Explanation means showing your steps so others can follow.

Example: Share the quick scoring sheet you used to pick a single. - Self-regulation means noticing bias and updating when facts change.

Example: you preferred A, blind tests point to B, you switch and write down why.

Try it today in ten minutes

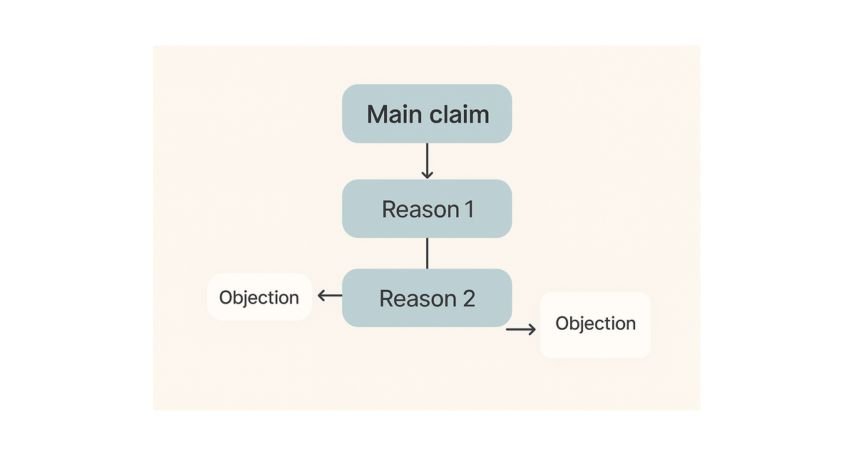

- Map a decision in two minutes. Draw a box for the claim, add reasons under it, and park objections on the side. Studies and program write-ups report gains in critical-thinking performance when learners practise argument mapping. For a clear research summary, see van Gelder’s chapter on argument mapping.

- Write your criteria first. Three checks that matter, for example clarity, fit, effort, with rough weights 5, 3, and 1. Choose after you score.

- Do a “claim, evidence, gap” pass. One line for what is said, one for what backs it, one for what is missing.

Why this practice sticks

- Small, timed drills are easy to repeat. A behaviour is more likely to happen when the ability is high and a clear prompt is present. Short, simple reps with a visible cue fit the bill, which is why five-minute drills tend to become habits.

- If-then plans boost follow-through. Writing “If it is 10:30, then I run Two-Minute Map” links a cue to an action. A meta-analysis across 94 studies reported medium to large effects on goal completion for these “implementation intentions.”

- Spaced practice makes gains last. Returning to drills on a schedule outperforms cramming for long-term memory, a result replicated across hundreds of experiments on the spacing effect.

- Testing yourself strengthens memory. Quick retrieval checks like “Claim, Evidence, Gap” or a one-minute recap produce better retention than re-reading alone. This is the testing effect.

- A bit of desirable difficulty helps. Light effort or generation makes learning stickier, so short maps, blind A/Bs, or scoring sheets are worth the friction.

Everyday scenes, and what to do

- You want a quick win.

Sketch a two by two impact and effort grid. Put each idea where it belongs, then pick the top left box first, high impact and low effort.

Example: four promo ideas go on the grid, a tidy email nudge lands as a quick win, a short film is high impact but heavy lift, schedule it rather than stall. - You want to avoid a repeat mistake.

Run a pre-mortem. Pretend the plan failed, list likely causes, and circle one you can act on this week. The original popular guide is Gary Klein’s Harvard Business Review article, useful for step by step prompts.

Example: “merch missed the tour” because stock got stuck in transit, put a second supplier on hold today. - You keep missing the root cause.

Try Five Whys until you hit something you can fix today. The ASQ page explains when to use it and how to pair it with other tools.

Example: missed deadline, approvals were late, no named reviewer, add a reviewer field to the brief.

A note on creativity

Creative thinking and critical thinking are not rivals. One generates options, the other pressure-tests them.

The APA entry on creativity is a useful counterpoint when you want language for idea generation, then you can use the checks above to decide what to keep.