We waited three years for Severance Season 2. Three years of theorising about what those goats meant, what Lumon actually does, and whether Mark’s wife really died. When it finally arrived in January, the show justified every single day of that wait.

The second season opens exactly where we left off, with Mark S running through Lumon’s labyrinth searching for Miss Casey, who his outie discovered is actually his supposedly dead wife, Gemma.

The disorientation carries through ten episodes that somehow answer questions whilst raising even more. We learn MDR isn’t just randomly sorting numbers. They’re building separate severed personalities, each trapped in their own nightmare scenario. One personality exists only at the dentist. Another one’s perpetually writing Christmas thank-you cards.

Episode four delivered the season’s biggest surprise: Helly wasn’t Helly at all. She’d been Helena Egan, daughter of Lumon’s CEO, spying on them the entire time. The revelation recontextualises everything we thought we knew about her character, and Britt Lower’s performance switching between the terrified innie and the calculating Egan heir is genuinely astonishing.

But it’s episode seven that elevates the season from great to essential. The flashback showing Mark and Gemma’s relationship: their romance, their failed attempts to have children, Gemma’s decision to volunteer for Lumon’s experiments.

It’s shot like a 1970s film and hits with devastating emotional weight. By the time we see what “Cold Harbor” actually contains (the unbuilt crib from their failed pregnancy), the show’s playing on a completely different level than nearly anything else on television.

Adam Scott gives a career-best performance playing essentially two versions of the same man who are becoming fundamentally different people. The finale’s confrontation between innie and outie Mark, communicating via messages left on an unsevered balcony, captures everything the show does brilliantly.

These aren’t just two personalities: they’re two people with fundamentally different lives, loves, and futures. When innie Mark chooses to run with Helly rather than help his outie’s wife escape, it’s heartbreaking precisely because both choices make complete sense.

The season ends on a freeze-frame of Mark and Helly running down a hallway, holding hands, smiling. Until they’re not. The final frame catches them mid-stride with that excitement gone, replaced by the dawning realisation they’re running toward nothing. There’s nowhere for them to go.

They exist only on the severed floor, and they’ve just made themselves Lumon’s primary targets. It’s a perfect encapsulation of what makes Severance special: hope and tragedy existing simultaneously, neither cancelling out the other.

But the real story of 2025 wasn’t just what aired. It was how we watched it. Weekly releases made a comeback, and for good reason. There’s something Severance and The Last of Us understood that most streaming shows forgot: anticipation matters.

Dropping everything at once means a week of conversation, then silence. Releasing weekly means months of theories, Reddit threads spiralling into madness, and actual suspense about what happens next.

The Last of Us Season 2 knew exactly what it was doing when it premiered in April. The show opened with that scene from the game, the one fans have been dreading since the second season got announced.

No build-up, no warning, just golf club and brutality in episode one. It was a bold choice that split the fanbase immediately. Some called it genius. Others said it ruined the entire season before it could breathe. Both camps spent seven weeks arguing about whether the show earned its gut-punch, and that’s exactly what great television should do.

Pedro Pascal barely appears in half the season, letting Bella Ramsey and Kaitlyn Dever (as Abby) carry the emotional weight.

The show makes you care about Abby even when you don’t want to, which is considerably harder to pull off than making Joel likeable. By the finale in late May, the internet was a warzone of people defending their chosen character. That kind of genuine debate doesn’t happen when you binge eight episodes in one night.

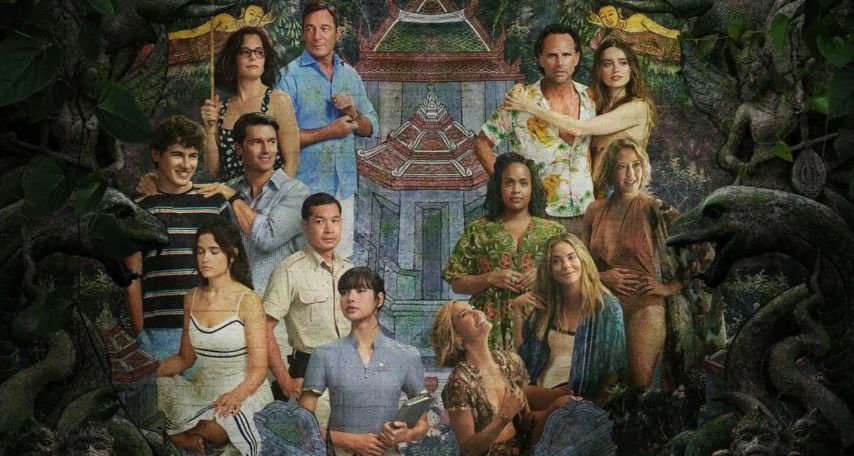

Mike White took The White Lotus to Thailand this year, and the change of scenery did nothing to dull his sharp eye for wealthy people behaving terribly. If anything, the cultural displacement made the satire even more uncomfortable.

Watching American and European tourists stumble through Thai customs whilst treating locals like set dressing hits different after Hawaii and Sicily’s more obviously colonial settings.

Episode five, titled “Full Moon Party,” delivered exactly what it promised. The ladies head out with Valentine and his crew for a night of questionable decisions. Jacqueline spots younger women on the dance floor who she believes are judging them for being out this late with younger guys. Her response? Getting more seductive with her dance moves, because nothing says “I’m secure in my choices” quite like proving something to strangers.

The episode brilliantly intercuts between two party groups spiralling in their own ways. Whilst the ladies take shots (except Kate, who smartly stays sober as the designated babysitter), we watch the boat party crew take mysterious drugs and things get progressively messier. Both storylines build toward the full moon working its magic on everyone’s worst impulses.

But the real standout belongs to Sam Rockwell’s Frank, who appears in Rick’s Bangkok storyline. The scene where Frank explains his journey to Buddhism might be the most uncomfortably fascinating monologue the show’s delivered yet.

What starts as Rick catching up with an old friend turns into Frank describing his obsession with Asian women, his spiral into sex and partying, and his realisation that maybe he wanted to become what he obsessed about.

The story gets progressively wilder as Frank details his path to self-discovery, eventually finding Buddhism as his way out. Rockwell commits fully to the speech, making something that could have been ridiculous feel disturbingly genuine.

The episode ends with multiple betrayals. Jacqueline, who spent all night playing wingwoman for Lorie and Valentine, ends up sleeping with Valentine herself.

Timothy nearly shoots himself before Victoria interrupts. The Ratliff brothers share a kiss that suggests Lachlan’s interest in his older brother goes beyond sibling rivalry. And Rick leaves with a gun in his bag, planning something violent for Jim.

Charlie Cox’s return as Daredevil in March should have been a disaster. Daredevil: Born Again had to bridge the gap between Netflix’s gritty street-level storytelling and Disney+‘s family-friendly MCU. The show went through production hell, fired its original showrunners, and reshot most of the first season. Yet somehow, it works.

The series leans into what made the Netflix show special whilst acknowledging it exists in a universe where gods and aliens regularly show up.

Matt Murdock’s legal cases carry actual weight again, and Vincent D’Onofrio’s Kingpin running for mayor creates stakes that feel grounded even when Daredevil’s fighting ninjas.

Episode six delivers the season’s most visceral hour. Matt finally dons the Daredevil suit after spending most of the season operating without it, driven by the kidnapping of Angela, White Tiger’s niece. The episode reveals Muse as a serial killer who’s used his victims’ blood to create elaborate murals across the city: 60+ victims and counting.

The show intercuts between two parallel fights: Matt hunting Muse through the city to save Angela, and Kingpin beating Adam with an axe in a sequence that’s uncomfortably brutal even by Netflix standards.

Matt saves Angela but lets Muse escape to prioritise her life, whilst Kingpin uses the chaos to form an anti-vigilante task force with corrupt cops. The tone walks a tightrope between dark and Disney, occasionally wobbling but rarely falling off completely.

The Pitt arrived in January promising to revolutionise medical dramas with its real-time format, and for a while, it genuinely does. Noah Wyle returns to hospitals after ER made him famous, this time playing Dr. Michael “Robby” Rabinavitch through 15 episodes that unfold as 15 continuous hours in a Pittsburgh trauma centre. The format isn’t just a gimmick. It’s the show’s soul.

Wyle’s performance is career-defining work, playing a doctor carrying trauma from COVID’s darkest days whilst maintaining the calm authority his ER needs.

The show strips away melodrama in favour of relentless pacing and medical accuracy that puts most hospital shows to shame. You feel the exhaustion accumulating, the way one patient’s crisis bleeds into the next, the mounting pressure of a system that’s perpetually understaffed and overwhelmed.

The ensemble cast matches Wyle’s intensity. Taylor Dearden’s anxious young doctor battling imposter syndrome, Tracy Ifeachor as an experienced physician hiding a devastating secret, and Isa Briones as a student who lacks bedside manner but possesses surgical brilliance.

Every character feels lived-in and authentic. When the show focuses on the actual medicine, on the impossible choices ER doctors face hourly, it’s some of the best medical television ever made.

But 15 hours is a long time to maintain that intensity. By episode ten, the format’s constraints start showing. The real-time conceit requires increasingly convenient plot contrivances to keep Wyle centre stage for every major case.

The finale’s mass casualty event delivers spectacle, yet you can’t help wondering: where’s the rest of the hospital? Why is the senior attending still handling everything?

The Pitt never quite becomes the disaster it could have been, but it can’t entirely justify its own ambition either. When it works, and it works more often than not, it’s a masterclass in procedural television. When it doesn’t, you’re left wishing they’d trusted the medicine enough to let the format breathe.

Dan Fogelman (the This Is Us creator) delivered Paradise in January, and it’s the kind of show that’s impossible to discuss without spoiling. Sterling K. Brown plays Secret Service agent Xavier Collins investigating the murder of a president in an underground bunker community. That’s all you should know going in.

The twist in episode three recontextualises everything, and whether it works depends entirely on your tolerance for high-concept sci-fi dressed up as political thriller. Personally? It’s the most interesting thing Fogelman’s done, even if it doesn’t always succeed at being all the things it wants to be.

Apple TV+ brought back The Morning Show for a fourth season in September, and honestly, it’s starting to feel like the show doesn’t know what it wants to say anymore. The first season had purpose, digging into #MeToo and workplace power dynamics.

Now it’s a prestige drama searching for relevance, throwing in storylines about corporate mergers and tech billionaires that never quite land. Reese Witherspoon and Jennifer Aniston still have chemistry, but even they can’t elevate scripts that mistake topicality for insight.

Star Trek: Strange New Worlds returned in July for its third season, proving once again that Trek works best when it tackles proper moral dilemmas. Episode six, “The Sehlat Who Ate Its Tail,” delivered exactly that kind of classic Trek storytelling.

Kirk finally gets what he wants when he takes command of the Farragut after Captain Varel gets critically injured. A massive scavenger ship destroys an entire planet and swallows both the Enterprise and Farragut whole. Kirk, eager to prove himself, pushes the engines to maximum warp against Scotty’s warnings. The result? The warp core fails completely, leaving them dead in the water.

The episode brilliantly captures that “be careful what you wish for” moment. Kirk spent the whole episode frustrated with Varel’s by-the-book captaincy style, wanting to take more risks. Now he’s got the captain’s chair in the worst possible circumstances, making panicked decisions that cripple his ship.

The crew has to MacGyver solutions with whatever they’ve got. Pelia digs out old rotary phones from her quarters (she apparently used to roadie for the Grateful Dead) so they can communicate when all systems get jammed. They’re literally shouting percentage commands through phone lines to manually control thrusters. It’s wonderfully clunky and desperate.

Then comes the painful twist. After Kirk destroys the scavenger ship, they discover 7,000 life signs in the debris. The “monster” ship turns out to be a lost 21st-century human colony vessel that’s been traveling for over a century. These people resorted to destroying planets to harvest fuel just to survive. Kirk just killed thousands of humans who were simply trying to stay alive.

The episode title refers to Spock’s Vulcan metaphor about a sehlat (Vulcan pet) that ate its own tail, similar to Kirk’s mom’s story about a dog chasing a car. Kirk wanted command so badly he didn’t think about what comes after you catch it.

Paul Wesley sells Kirk’s arc from cocky to horrified beautifully, and his scene with Spock discussing the weight of command feels like watching their iconic dynamic take root.

The real event, though, arrived in late November. Stranger Things kicked off its final season, splitting the conclusion across three releases. The first four episodes dropped on November 26th, and they’re… fine?

Look, Stranger Things peaked in season one. Everyone knows this. But there’s something bittersweet about watching the Hawkins gang grow up one last time. The Upside Down looks appropriately apocalyptic, the nostalgia hits land (mostly), and the young cast proves they’ve become genuinely skilled actors. Whether the show can stick its landing remains to be seen, but at least it’s going out with ambition.

So what did 2025 actually teach us? That patience pays off, for one. Severance took three years between seasons and delivered something worth the wait. That weekly releases create better conversations than binge drops. That franchise television can work when shows remember why people cared about the characters in the first place.

But mostly? That we’re drowning in content but starving for shows that take genuine risks. The Last of Us opened with a beloved character’s death because it trusted audiences to handle it. Severance refuses to explain itself, demanding you pay attention and think. Even The White Lotus, for all its prestige trappings, isn’t afraid to make its characters genuinely unlikeable.

Compare that to The Morning Show spinning its wheels or The Pitt collapsing under the weight of its own concept. The difference isn’t budget or talent. It’s whether the people making television believe in what they’re doing, or whether they’re just filling hours on a streaming service.

2025 wasn’t television’s golden age. But it gave us enough genuinely great television to remind us what the medium can do when it stops trying to be everything to everyone. Sometimes that’s enough.

You might also like:

- The 10 Most-Watched TV Shows in the UK This Week—And Why You Need to Tune In

- Squid Game’s Biggest Twist: Gi-hun’s Not the Hero Anymore

- The Best Sci-Fi Movies on Amazon Prime Video

- From Season 2 TV Series Explained: A Deep Dive into Theories, Plotlines, and Future Speculations

- Top 5 TV Shows With Iconic Theme Songs

- About Sydney Sweeney, the Emmy-Nominated Actress from Euphoria and The White Lotus

- Best Vampire Movies and TV Shows of All Time