Most people learn at some point that nursery rhymes are not quite what they seem. Ring a Ring O’ Roses is supposedly about plague.

London Bridge involves child sacrifice. Oranges and Lemons ends with an execution. The internet has been repeating these theories for years and, honestly, some of them are more reliable than others.

Here is a quick rundown before we get into the details:

- Ring a Ring O’ Roses – widely claimed to be about the Black Death, probably is not

- London Bridge Is Falling Down – the bridge really did keep falling down, though darker versions involve children buried in the foundations

- Oranges and Lemons – the final lines about a chopper were added later and almost certainly refer to public executions at Newgate

- Humpty Dumpty – more likely 17th and 18th century slang than either an egg or a Civil War cannon

- Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary – Bloody Mary, Protestant martyrs and a garden that may be a graveyard

- Three Blind Mice – three bishops burned at the stake in Oxford

- Baa, Baa, Black Sheep – medieval wool tax, genuine grievance, surprisingly direct

- Goosey Goosey Gander – Catholic priests hiding in priest holes during the Reformation

- Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush – women exercising in circles at Wakefield Prison

- Jack and Jill – possibly Charles I altering liquid tax measures

- Rock-a-Bye Baby – the disputed parentage of James II’s Catholic heir

Some of these are solid history. Some are theories repeated often enough to become accepted wisdom. A few are almost certainly invented. The more interesting question is not just what the rhymes mean, but why the dark readings have such staying power even when the evidence is thin.

Ring a Ring O’ Roses

The plague theory is almost certainly wrong, which is annoying because it fits so neatly.

The idea goes like this: the rosie is the rash, the posies are the herbs people carried to ward off infection, the sneezing is a symptom, and “we all fall down” means everyone dies.

It maps perfectly onto a medieval epidemic narrative and sounds like exactly the kind of thing passed down through generations.

Except there is no actual evidence for it. Not a single contemporary account, diary entry or record connects this song to either the Great Plague of 1665 or the Black Death of the 1340s.

The plague reading did not appear until the 1950s, centuries after either event. The folklorist Peter Opie, who spent much of his career tracing nursery rhyme origins, could not find anything to support it.

Older versions do not include sneezing. Some end with everyone standing back up.

The most likely reading is that it is a circle game, probably about courtship. The falling down might be a curtsy. The rosie might simply be a rose.

Similar versions appear across Germany, Switzerland and Italy, suggesting an older and probably innocent origin in children’s circle games rather than English pestilence.

The internet prefers the plague explanation. Folklore scholarship does not. Iona and Peter Opie, whose Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes remains the standard reference, found no contemporaneous source connecting the song to any epidemic. The plague theory only appears in print in the mid-20th century.

London Bridge Is Falling Down

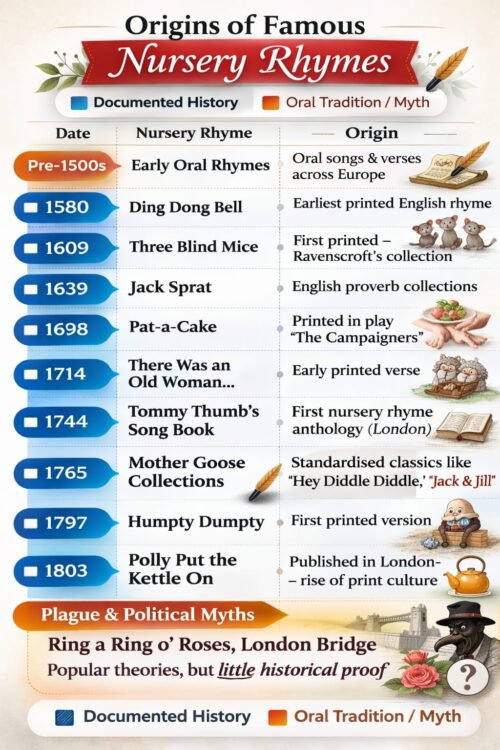

London Bridge genuinely kept falling down. It was damaged by ice in 1281, set alight during the Great Fire in 1666 and required constant repair for much of its life. Bad materials, bad maintenance and chronic underfunding are enough to explain the rhyme.

The Viking theory is more dramatic. It connects the song to 1014, when Olaf II of Norway reportedly attacked London and destroyed the bridge.

A 13th century Norse saga appears to support this, but the evidence is fragile. Samuel Laing’s 19th century translation reads, “London Bridge is broken down, gold is won and bright renown.”

That sounds remarkably like the nursery rhyme. Too remarkably. Later translators produced versions that barely resemble it. The similarity is likely Laing’s embellishment, not medieval prophecy.

There is also the ritual sacrifice reading. The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes suggested the song may preserve “the memory of a dark and terrible rite.” In parts of medieval Europe, folklore held that bridges required a human life sealed within their foundations to stand firm.

Old versions of the rhyme include the line “take the key and lock her up.” Not lock something up. Lock her. In this interpretation, the “fair lady” is not symbolic but literal.

During excavations near the London Dungeon in 2007, human remains were discovered close to old bridge foundations. Whether they were placed there deliberately is impossible to determine. But they were there.

Oranges and Lemons

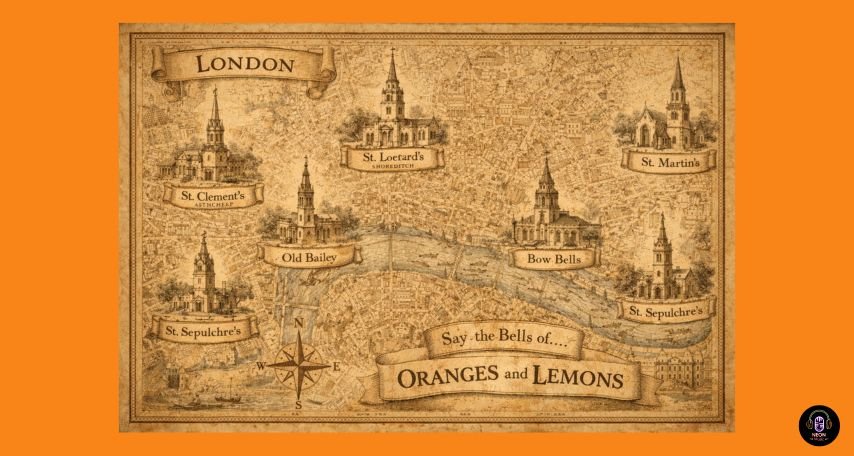

The churches named in the rhyme are real, and the bell sounds attributed to them may reflect actual pitches. That part likely functions as a musical map of the City of London.

The final lines are another matter. “Here comes a candle to light you to bed, here comes a chopper to chop off your head” were not in early versions. They appear to have been added in the 18th or 19th century and likely reference public executions.

Condemned prisoners at the Old Bailey were visited the night before hanging by the bell man of St Sepulchre’s Church, who carried a candle and rang a handbell outside the cell. The candle to light you to bed. The execution the next morning.

The children’s game that accompanies the rhyme involves two players forming an arch and dropping it at the word “head,” trapping whoever passes beneath. It is children reenacting execution ritual, wrapped in melody.

Henry VIII’s wives are sometimes suggested because Tudor beheadings are always compelling. But the rhyme’s structure, moving through City churches toward the Old Bailey, points far more convincingly to Newgate Prison.

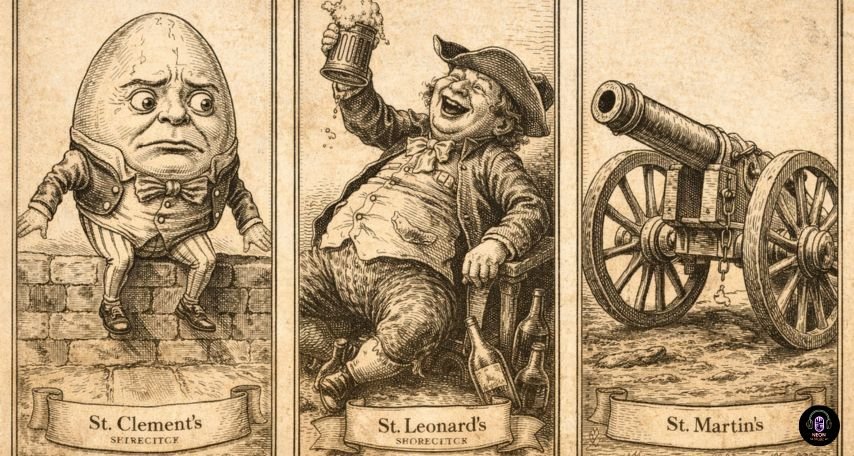

Humpty Dumpty

Humpty Dumpty as an egg is relatively recent. Lewis Carroll illustrated him that way in Through the Looking Glass in 1871. Before that, the rhyme functioned as a riddle. What, once broken, cannot be repaired?

The answer was an egg. But the character did not have to be one.

The Civil War cannon theory suggests Humpty Dumpty was a Royalist cannon that fell from Colchester’s walls during the 1648 siege. The problem is straightforward: no contemporary document calls any cannon “Humpty Dumpty.”

Another reading links the name to slang. In the 17th and 18th centuries, “Humpty Dumpty” referred to a drink made from brandy boiled in ale and also described short or clumsy people. That usage is historically attested.

Of the competing explanations, the slang origin is the most solidly grounded. Which may be why it is the least dramatic.

Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary

This rhyme has gathered at least three interpretations.

One sees it as a Catholic allegory about the Virgin Mary. Another links it to Mary Queen of Scots. The darkest reading casts it as satire aimed at Mary I of England, known as Bloody Mary.

In that version, the “silver bells” are thumbscrews, the “cockle shells” instruments of torture and the garden a graveyard of Protestant martyrs.

Mary I burned more than 280 Protestants at the stake in under five years. “How does your garden grow?” reads very differently in that context.

There is no definitive answer. But the Bloody Mary reading persists because it aligns cleanly with documented violence.

Three Blind Mice

First printed in 1609 in Deuteromelia, this is one of the earliest nursery rhymes with a confirmed publication date.

The theory linking it to Hugh Latimer, Nicholas Ridley and Thomas Cranmer, burned under Mary I between 1555 and 1556, came later. The timeline does not rule out oral circulation, but it does prevent certainty.

The rhyme is written as a round. Voices overlap and echo each other. Public burnings were also communal events. Whether deliberate or accidental, the structural similarity is difficult to ignore.

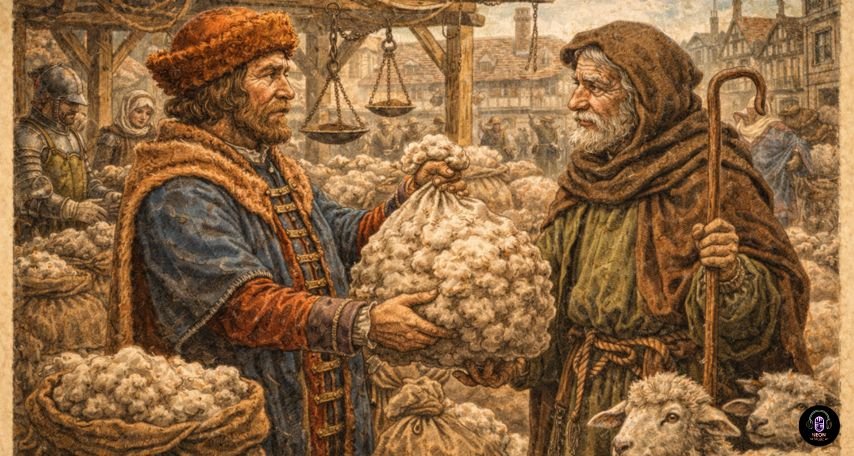

Baa, Baa, Black Sheep

This rhyme has solid historical footing.

In 1275, Edward I introduced the Great Custom, a wool export tax dividing proceeds between crown, church and merchant. Master, dame and little boy.

Some early versions include the line “and none for the little boy who cries in the lane,” making the grievance explicit.

The slavery interpretation lacks evidence. The wool tax explanation requires no imaginative leap and aligns directly with documented economic policy.

Goosey Goosey Gander

The unsettling final verse about throwing a man down the stairs may have originated separately.

During the Reformation, Catholic priests hid in secret chambers known as priest holes. Nicholas Owen, a master builder, constructed many of them.

An old man found refusing Protestant prayers and dragged by his left leg reads differently in that light. Whether it records a specific event or borrows the texture of authenticity, the context is real.

Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush

R.S. Duncan, former governor of Wakefield Prison, claimed the rhyme originated with female prisoners exercising around a mulberry tree in the yard.

The prison dates to 1594. The tree stood for over four centuries before dying in 2017. A cutting has since been replanted. The prison crest features a mulberry.

Whether the rhyme began there or attached itself to a vivid story later is uncertain. But the location exists.

Jack and Jill

The Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette reading fails on dates alone. The rhyme appeared in print in 1765. The guillotine fell in 1793.

The Charles I theory is more plausible. Jack and gill were liquid measures. When Charles I reduced their size while maintaining the rate, the “jack fell” and the “gill came tumbling after.”

Less cinematic. More historically coherent.

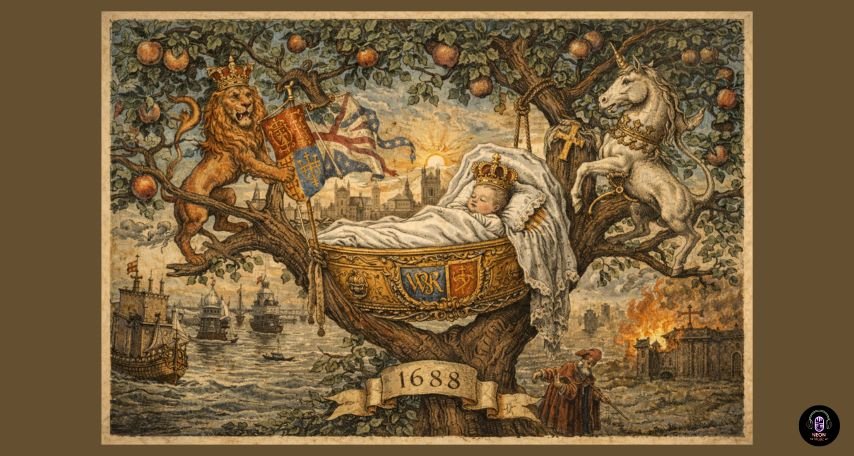

Rock-a-Bye Baby

As a lullaby, this is a strange choice.

One theory connects it to the warming pan scandal of 1688, when James II’s Catholic heir was rumoured to have been smuggled into the birthing chamber.

In that reading, the treetop represents precarious succession. The wind is Protestant pressure. The breaking bough is the Glorious Revolution.

It is one of the better grounded political interpretations on the list. It still does not explain why anyone would sing it to a child.

Why the Dark Readings Stick Even When They’re Wrong

The plague reading of Ring a Ring O’ Roses is likely invented. The guillotine reading of Jack and Jill collapses under chronology. The cannon story of Humpty Dumpty lacks contemporary documentation.

And yet they endure.

Nursery rhymes are short, repetitive and portable. They were built to travel through communities that could not always write things down. Once you know that, every ambiguity starts to look like code.

Worth noting: the darker the theory, the later it tends to appear in the historical record.

The plague reading is mid-20th century. The guillotine reading requires ignoring print dates. The theories with the strongest historical grounding, the wool tax, the Oxford Martyrs, the Newgate executions, appear closer in time to the events they describe.

Most credible dark readings cluster around the Tudor and Stuart periods. That likely says less about those centuries being uniquely secretive and more about modern fascination with monarchy, execution and religious violence.

Some projections uncover genuine history. Others are folklore about folklore.

The songs are too old and too deeply embedded to cleanly separate original meaning from later imagination. At this point, both are part of the story.

You might also like:

- It’s Raining, It’s Pouring Meaning Unveiled: Decoding the Ominous Undertones of the Nursery Rhyme

- 1 2 Buckle My Shoe” or simply “nursery rhyme trends

- Disney Songs With Hidden Meanings You Never Noticed As a Kid

- The Ghost of the Goon: When a Meme Haunts More Than Just the Internet

- The Mystery and Melancholy of Bobbie Gentry’s Ode to Billie Joe

- Greased Lightnin’: The Hidden Sexuality Behind the Classic Hit Song