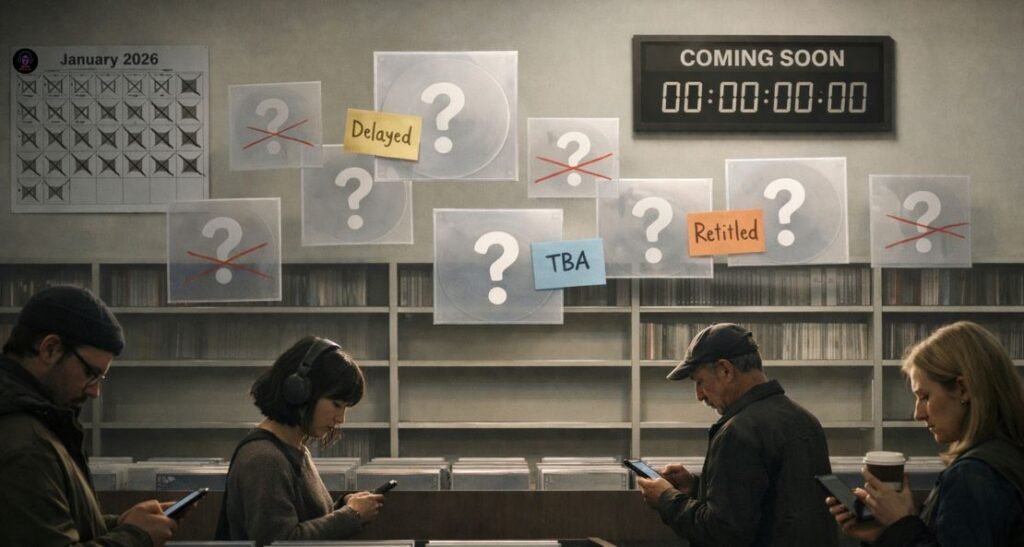

Some albums exist longer as rumours than as released music. Sky Ferreira has appeared on every “most anticipated” list since 2018.

Frank Ocean’s follow-up to Blonde became a punchline years ago. At some point, the anticipation becomes the product itself, a perpetual state of almost that generates more conversation than the music ever could.

Welcome to 2026, where half the year’s most anticipated albums will probably get postponed again.

Lana Del Rey’s Infinite Postponement Cycle

Stove was supposed to be Lasso. Before that, it was The Right Person Will Stay. Lana Del Rey’s tenth studio album has undergone more identity crises than actual confirmed recording sessions.

September 2024 came and went. May 2025 dissolved into vague promises. Now we’re looking at “late January 2026” according to her W Magazine interview, though anyone familiar with Lana’s relationship with wistful nostalgia and perpetual reinvention knows that’s optimistic at best.

She’s working with Jack Antonoff, Drew Erickson, and country producer Luke Laird on what she describes as “Western-influenced” material that’s “more autobiographical than I thought.”

That biographical element apparently required time (enough to marry, relocate, and rethink the entire direction multiple times).

She’s teased tracks like “Stars Fail on Alabama” and “Quiet in the South” at Coachella, offering glimpses without commitment.

The pattern is familiar by now. Announce a date, preview some songs, shift the concept, rename the project, push everything back. Chemtrails Over the Country Club followed this script. So did Did You Know There’s a Tunnel Under Ocean Boulevard.

The music arrives eventually, usually excellent, always late. The question isn’t whether Stove will be good. It’s whether it’ll actually be called Stove when it finally drops, or if we’ll get another rename in March.

Eight Years Since A$AP Rocky’s Last Album

Eight years separates Testing from Don’t Be Dumb, A$AP Rocky’s fourth album finally scheduled for 16 January.

That’s two full presidential terms, multiple Drake albums, the entire rise and cultural saturation of hyperpop.

Legal troubles, a shooting trial acquittal, and fatherhood filled the gap, but the core question remains: can you disappear for eight years and return like nothing happened?

“Punk Rocky,” the lead single, suggests Rocky isn’t particularly interested in announcing himself loudly.

The track ditches cloud rap for psychedelic indie shimmer (jangly guitars, crash cymbals, Tame Impala production courtesy of Zach Fogarty).

It’s pretty, melancholic, entirely lacking urgency. “She don’t even wanna be my wife no more / Got me crying in the microphone,” Rocky admits over washed-out instrumentation that sounds nothing like 2018.

The title oversells itself. This isn’t punk rock. It’s downtempo indie with surf undertones and breathy vocals that prioritise atmosphere over impact.

For a comeback single meant to reestablish Rocky’s relevance after nearly a decade, “Punk Rocky” barely raises its voice, which might be the problem or might be the point depending on whether you think restraint equals artistic evolution or just creative fatigue.

Production lineup includes Pharrell Williams, Mike Dean, and Metro Boomin, with singles like “Riot,” “Hijack,” and “Taylor Swift” previewed over the years.

Nobody knows which tracks actually made the final album. The rollout has been chaotic, the messaging unclear, the whole project existing in a strange limbo between confirmed and theoretical. January will either validate the wait or expose it as wasted time.

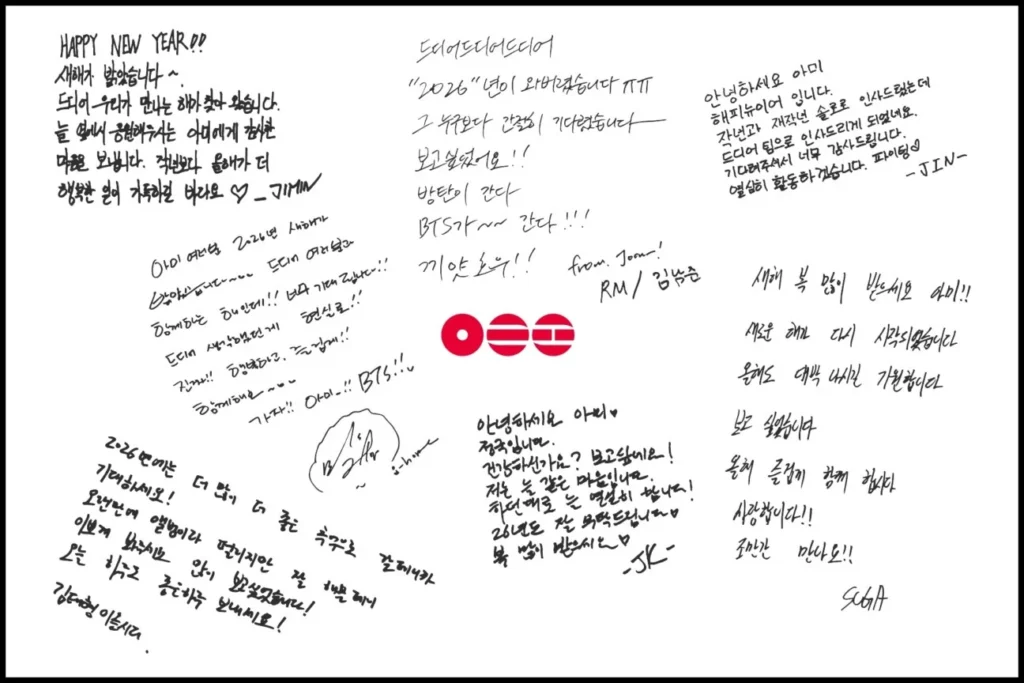

BTS Returns From Military Service (And Everything’s Changed)

Twenty March marks BTS’s first release since mandatory South Korean military service pulled all seven members offline for nearly three years.

The stakes feel existential. K-pop didn’t pause during their absence. It accelerated. Blackpink’s Rosé scored over a billion streams with “APT.” featuring Bruno Mars, and the genre’s global penetration reached new heights without BTS leading the charge.

Their return tests whether enforced hiatus strengthens anticipation or creates space for replacement. Big Hit confirms 14 tracks recorded in Los Angeles with Jon Bellion, material “driven by each member’s honest introspection as they collectively shaped its direction.”

That phrasing suggests cohesion despite years apart, individual growth channelled into group vision.

But three years is geological time in pop music. Fanbases fracture, solo projects dilute collective identity, and the members pursued individual work during service that carved separate lanes and potentially separate audiences.

Reassembling those pieces into unified momentum isn’t guaranteed just because everyone wants it to happen.

The album’s success won’t just determine BTS’s commercial viability. It’ll answer whether absence still creates desire when fans have endless content alternatives, whether the mythology of reunion requires scarcity to function, whether waiting still intensifies longing or just gives audiences permission to move on.

You might also like:

- Best Albums of 2025: Critics & Fans Agree

- Charli XCX “Chains of Love” Review: Gothic Pop Perfection

- Charli XCX’s Everything Is Romantic: How a Vulnerable Track Became Brat’s Unexpected Moment

- A$AP Rocky – Punk Rocky Review

- Best Lana Del Rey Songs: The Soundtrack of Summertime Sadness and Nostalgic Beauty

- Album Formats And How They Have Changed Over The Years

Charli XCX Does Everything Wrong on Purpose

“My next record will probably be a flop which I’m down for,” Charli XCX told Culted months after Brat became a cultural phenomenon.

Wuthering Heights, her soundtrack companion to Emerald Fennell’s Emily Brontë adaptation, drops 13 February and immediately makes good on that promise.

This isn’t Brat 2. This is Charli using film work as permission to abandon everything that just succeeded.

Lead singles “House” and “Chains of Love” trade hyperpop’s confrontational energy for Gothic atmospheres and orchestral arrangements.

Producer Finn Keane (who crafted “Von Dutch” and “Sympathy Is a Knife”) stripped away maximalism, replacing it with sweeping strings that feel simultaneously expansive and claustrophobic.

Charli’s vocals remain controlled, measured, creating tension between lyric rawness and performance restraint.

“My face is turning blue / Can’t breathe without you here / The chains of love are cruel / I shouldn’t feel like a prisoner,” she sings on the title track.

The metaphor lands somewhere between obvious and effective, articulating toxic attachment with production that suffocates intentionally.

This is Charli at her most vulnerable and least immediately accessible.

Following Brat‘s mainstream breakthrough with something deliberately smaller could read as artistic courage or commercial self-sabotage. T

he film provides cover (soundtrack work carries different expectations, operates under different commercial pressures), but whether Wuthering Heights registers as evolution or retreat depends entirely on whether audiences grant her the creative freedom she’s claiming for herself.

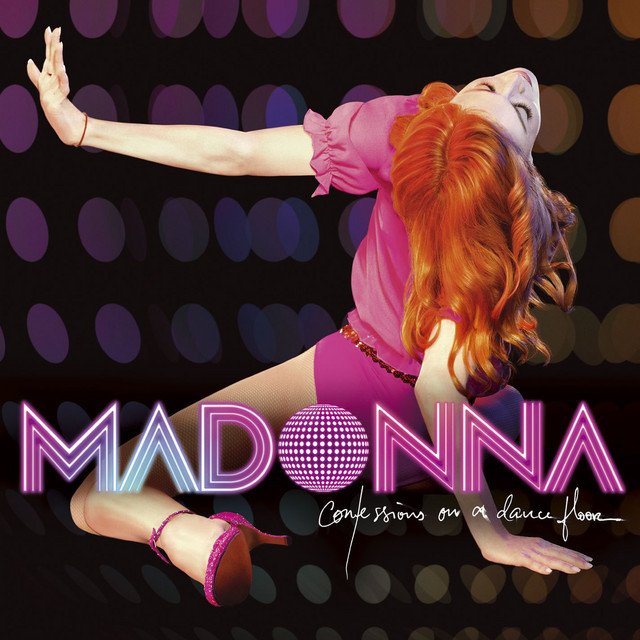

Madonna Tries to Recapture 2005

Confessions on a Dance Floor Part 2 arrives sometime in 2026, two decades after the original spawned “Hung Up” and earned Madonna a Grammy for best electronic dance album.

Stuart Price returns as producer, which either suggests faithful sequel energy or creative stagnation depending on your perspective.

The original worked because Madonna hadn’t fully committed to dance music’s late-2000s resurgence yet. She arrived early, claimed the sound before it peaked, shaped its mainstream direction.

Returning now positions her as legacy act rather than innovator, coming back to a landscape where dance-pop has cycled through multiple iterations and EDM festival culture has risen and declined.

“Popular” with The Weeknd and Playboi Carti proved she can still score hits (1.2 billion Spotify streams doesn’t lie), but guest features and album vision are different challenges.

Madame X (2019) received respectful reviews without generating lasting cultural conversation. Madonna’s continued relevance depends on whether Confessions Part 2 feels like creative statement or greatest hits cosplay.

The danger isn’t that she can’t make good dance music. It’s that revisiting past triumphs draws attention to how much the landscape has shifted.

Twenty years ago, Madonna defined the sound. Now she’s competing with artists who grew up on Confessions and absorbed its lessons into their own work.

The Albums That Probably Won’t Happen

Rihanna’s R9 appears on every list despite zero concrete evidence. She’s released exactly one song since 2023’s “Lift Me Up” (a Smurfs soundtrack cut called “Friend of Mine”).

During a Met Gala interview, she insisted pregnancy hadn’t delayed recording: “Maybe a few videos, but I could still sing.” That was her last public comment on new music.

View this post on Instagram

A decade separates us from Anti, an album that demonstrated Rihanna’s artistic vision whilst achieving commercial dominance.

Her continued absence suggests either extreme perfectionism or complete disinterest in returning to music, and at this point it’s impossible to tell which.

Either way, R9 functions better as myth than release. The anticipation generates more conversation than the album probably could.

Frank Ocean’s theoretical follow-up exists in similar territory. Blonde turned 10 last August. He’s released scattered singles, appeared on others’ tracks, stayed largely silent.

Billboards near Coachella last year fuelled rumours that turned out false. The next Frank Ocean album exists primarily as concept now, something fans reference as cultural shorthand for artistic absence rather than actual forthcoming music.

The lists include these artists anyway because exclusion feels like admitting defeat. Better to acknowledge the impossibility than accept these albums may never exist.

Why Everyone’s Suddenly Changing Genres

Charli ditches hyperpop for Gothic soundtrack work. Lana leans into Western Americana.

Gorillaz’s The Mountain (27 February) was recorded in India with posthumous features from Dennis Hopper, Bobby Womack, and D12’s Proof, because Damon Albarn remains committed to defying categorisation even when it makes no commercial sense.

These shifts function as creative resets but also strategic repositioning. Following a massive success with something sonically different reduces the pressure of sequential comparison.

If Wuthering Heights underperforms, it’s because it’s a soundtrack album, not because Charli lost her touch.

If Stove doesn’t match Ocean Boulevard‘s critical reception, well, it’s country-influenced material appealing to different audiences.

Genre becomes protective camouflage. Artists can experiment without risking their core brand equity, claim artistic evolution whilst maintaining commercial escape routes.

The streaming era enables this fluidity because playlists don’t require sonic consistency, algorithms surface individual tracks regardless of album context, and an artist can release a Gothic indie album and a hyperpop banger in the same year without confusing anyone.

The Waiting Might Be the Point

Here’s what 2026’s anticipated albums actually reveal: consistency doesn’t matter anymore. Bad Bunny releases constantly and dominates year-end lists.

A$AP Rocky disappears for eight years and still commands attention. Both strategies work because audiences fragment across contradictory preferences, and the algorithm rewards everything and nothing simultaneously.

BTS commands attention after three years silent. Rihanna generates speculation after a decade mostly absent.

Madonna remains culturally relevant despite streaming numbers that pale against contemporary pop stars.

Legacy and mythology matter as much as actual music, which explains why half these albums could get postponed again without the anticipation really diminishing.

The “most anticipated” lists used to predict what we’d actually be listening to by December.

Now they document which artists retain enough cultural capital to make people care about albums that may never arrive.

Album formats have changed dramatically over the decades, but the weirdest shift might be this: the album doesn’t need to exist for the story to continue.

Lana will probably rename Stove again before it drops. Rocky’s comeback might land with a thud. BTS could fracture under the weight of expectation.

Charli might actually get the flop she’s claiming to want. Or everything could exceed expectations and none of this speculation will have mattered.

Either way, we’ll be having the exact same conversation in January 2027, adding Sky Ferreira to another list, wondering if Frank Ocean’s next album is finally coming, debating whether the gaps between releases still build mystique or just create indifference. The albums might eventually arrive. The waiting definitely will.