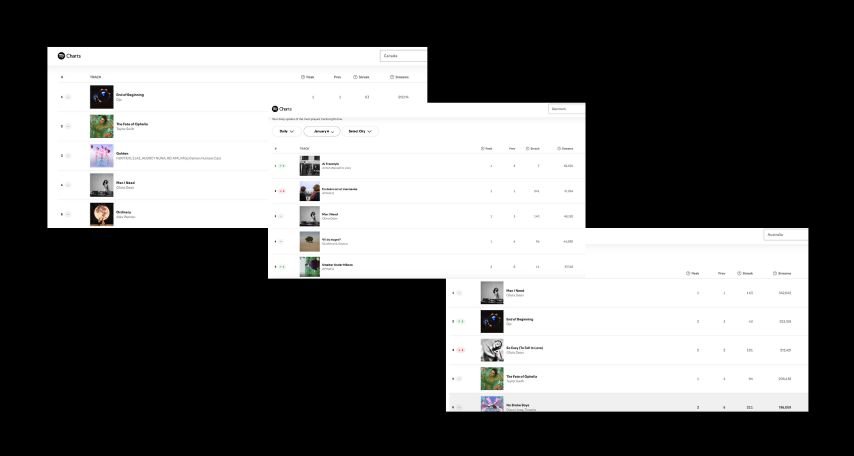

Fifty-five per cent of Britain’s Spotify charts belong to American artists. Twenty-nine per cent go to British ones.

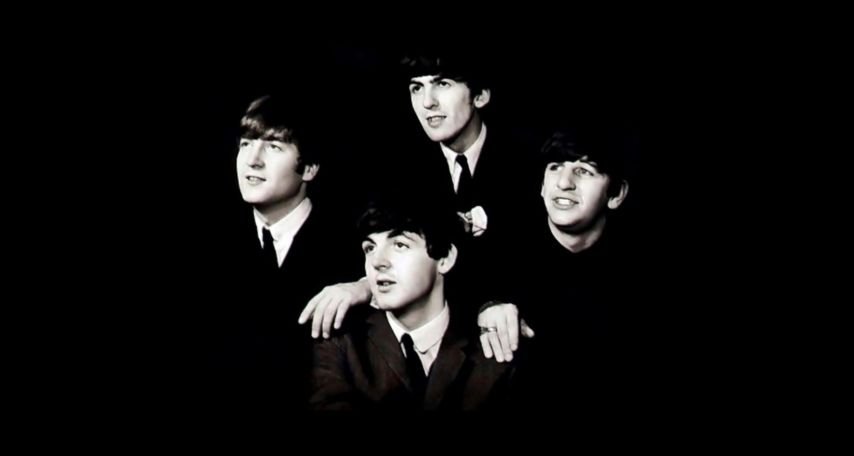

In the country that gave the world The Beatles, David Bowie, and Amy Winehouse, UK charts show American dominance reaching levels that would’ve seemed impossible a generation ago.

Britain ranks 39th out of 73 countries for supporting domestic artists. Thirty-ninth. Behind Hungary. Behind the Czech Republic. Behind Iceland, a nation with fewer people than Nottingham.

Yet Britain ranks fifth globally for streaming American music, which means British listeners don’t just tolerate US dominance. They actively choose it.

Year-long analysis of Spotify’s Top 200 charts across 73 countries reveals Britain as one of the world’s most American-friendly music markets and one of the least protective of its own.

The data spans over 800,000 data points from May 2024 to July 2025, documenting how algorithmic curation reshapes musical identity at scale.

The European Comparison Nobody Wants

Italy keeps 83% of its charts domestic. France holds 60%. Germany manages 48%. Even Spain, with its 28% domestic share, outperforms the UK’s 29%.

The pattern shows language doesn’t determine outcome. Spain speaks Spanish, yet British artists claim more Spanish chart territory than Spanish artists claim British territory.

Language advantage works both ways, except it doesn’t work equally. Americans benefit from English ubiquity. British artists theoretically share that advantage but fail to convert it at home.

What Italy does differently matters. Italian hip-hop dominates Italian charts because Italian audiences demand Italian perspectives on Italian contexts.

Geolier’s 5% individual chart share in a single country exceeds what most British artists achieve in their own market.

When your music speaks to specific lived experience rather than universal export-friendly themes, local audiences notice.

The UK music industry generates billions in export revenue. British artists appear in the Top 5 music sources for 42 out of 73 countries analysed. Ireland streams 24% British music. New Zealand 16%. Australia 15%. Britain feeds the global ecosystem whilst starving at home.

That interpretation isn’t as clean as it looks. Maybe British artists succeed globally precisely because they don’t prioritise domestic markets.

Maybe chasing American approval creates export-ready product. If you design music to work in Des Moines, it’ll probably work in Dublin too. Design it for Doncaster and you might limit international appeal.

The data suggests British artists make that calculation and accept the trade-off.

What Algorithms Actually Do

Streaming recommendation systems don’t distinguish languages. They track engagement patterns. When algorithms can’t identify linguistic preferences, they default to popularity metrics that favour established American stars with massive global followings.

Spotify’s “Discover Weekly” and “Daily Mix” playlists analyse your listening history and serve similar music. But “similar” increasingly means “popular in markets you demographically resemble” rather than “from artists in your country”.

A British listener who enjoys pop gets Taylor Swift, not RAYE. Someone who streams hip-hop receives Kendrick Lamar, not Dave.

The mechanism reinforces itself. American artists with hundreds of millions of streams generate more data points for algorithmic training.

More data means better recommendations. Better recommendations mean more streams. The feedback loop compounds American advantage whilst British artists struggle to generate the critical mass needed for algorithmic visibility.

TikTok complicates this further. Viral moments favour tracks that work across cultural contexts without explanation.

Jess Glynne’s “Hold My Hand” dominated summer 2025 not because it was distinctly British, but because it worked for holiday montages globally. British artists achieve virality by sanding off Britishness until only universal relatability remains.

The Language Advantage That Isn’t

English should help British artists. It doesn’t, or at least not enough to matter. Americans export English-language music globally. British artists export English-language music globally.

Both compete in the same linguistic space. Americans win because they’ve built industrial infrastructure that Britain can’t match.

US labels invest in playlist placement, radio promotion, and strategic partnerships at scale British labels don’t attempt.

Major American releases coordinate global campaigns across dozens of markets simultaneously. British campaigns typically go UK-first, then hope for international pickup.

That three-month gap gives American artists time to establish dominance before British competition arrives.

The Grammy Awards and Billboard charts function as global cultural arbiters in ways the BRIT Awards and UK Official Charts don’t.

When an American artist wins a Grammy, Asian markets pay attention. Latin American markets pay attention. European markets pay attention.

When a British artist wins a BRIT, Britain pays attention. Maybe Ireland if they’re lucky. The cultural legitimacy gap compounds commercial disadvantage.

Consider the 2024-2025 UK streaming data. The 30 artists who dominated UK charts include Ed Sheeran, Dua Lipa, Harry Styles, and Adele.

They are all British superstars, yet they share chart space with Taylor Swift, The Weeknd, Billie Eilish, and Ariana Grande at ratios that favour Americans roughly 2:1.

British artists can achieve individual success. They cannot achieve collective dominance in their home market anymore.

When Domestic Support Dies

The 1960s British Invasion succeeded not through mimicking American music but by offering something unmistakably British the world hadn’t heard.

The Beatles brought Liverpool. The Rolling Stones brought blues filtered through London. David Bowie brought theatrical experimentalism that could only emerge from British art school culture.

Modern British chart success requires different maths. Lewis Capaldi dominates through emotional ballads that work in Nashville as easily as Newcastle.

Harry Styles crafts Laurel Canyon rock that Californians claim as their own. Dua Lipa makes disco-pop designed for global playlists. The exports succeed. The identity fades.

If British artists can’t top their own charts, what does that mean for Britain’s next musical revolution?

The uniquely British sounds get marginalised before they reach commercial viability. Grime took a decade to penetrate mainstream British charts and never achieved sustained dominance.

UK garage remains nostalgic rather than current. Britpop ended 25 years ago. Nothing distinctly British has dominated British charts since, which might explain why nothing distinctly British dominates global charts anymore either.

The streaming model rewards scale over specificity. Regional sounds that might thrive in radio-era ecosystems now compete against global superstars with unlimited shelf space.

A Manchester band that would’ve built local following through club gigs and regional radio now launches directly into algorithmic competition with Post Malone’s entire catalogue.

The ladder disappeared. You either start at the top or don’t climb at all.

The Economic Reality

British artists appear in 42 countries’ Top 5 music sources. Britain exports musical culture successfully.

But export success doesn’t guarantee domestic presence, and domestic presence increasingly determines whether artists achieve financial sustainability. Streaming royalties depend on total plays.

A British artist with 100,000 UK streams generates less income than an American artist with 100,000 US streams because US streams typically pay better rates due to higher subscription costs and different licensing deals.

But both earn dramatically less than an artist with 2 million streams globally, regardless of home market performance.

This creates perverse incentives. British artists who want financial viability must prioritise American approval over British audiences.

American market access determines career survival. British market presence becomes secondary, which accelerates the cycle that creates 55% American dominance to begin with.

The labels understand this perfectly. Investment decisions favour artists who can break America, not artists who might win Britain. Marketing budgets flow to potential global exports, not domestic specialists.

When EMI signs a British artist, they evaluate American commercial potential before considering British audience.

The industry abandoned domestic music culture in favour of export economics decades ago. The streaming data simply reveals what was already happening.

You might also like:

- Best Albums of 2025: Critics & Fans Agree

- Are Music Charts Even Relevant Anymore?

- How Much Do Artists Make on Spotify in 2025?

- Sleep Token NYT Song of Year 2025

- Apple Music Replay 2025: Complete Guide

- Songs That Took Over Spotify & TikTok December 2025

What British Listeners Actually Want

The uncomfortable truth is that British listeners keep voting for America. The data shows what British audiences chose across 800,000+ data points.

They chose Taylor Swift over RAYE. Kendrick Lamar over Dave. Billie Eilish over Olivia Dean. Individual taste reflecting collectively as American preference.

But taste doesn’t form in a vacuum. Playlist placement shapes discovery. Radio programming influences familiarity.

Marketing spend determines visibility. British listeners choose American artists partly because algorithms, playlists, and promotion present American artists as default options.

When you open Spotify’s Today’s Top Hits, you encounter American dominance before making any choice.

The Skoove analysis notes that streaming platforms may inadvertently accelerate transatlantic takeover through recommendation systems.

But “inadvertent” understates the mechanism. Platforms optimise for engagement, not cultural diversity. If American artists generate higher engagement (they do), algorithms will surface them more frequently.

The platforms aren’t accidentally preferring Americans. They’re mathematically obligated to.

Which raises uncomfortable questions about what preservation of domestic music culture means in algorithmic ecosystems. Radio had geographic constraints that forced local representation.

Commercial stations needed local listeners, which meant playing local artists. Streaming removes geography. Spotify doesn’t need British listeners to favour British artists.

It needs British listeners to stream more, and if Americans achieve that better, the algorithm does its job.

British listeners wanting to support British music face structural disadvantages. Discovery mechanisms favour American artists.

Marketing presence skews American. Cultural legitimacy markers point American. Chart success requires American approval.

The entire ecosystem pushes British audiences toward American choices, then treats those choices as authentic preference deserving algorithmic reinforcement.

The Chart Data That Matters

Recent UK Spotify charts show occasional British breakthrough. Olivia Dean occupied twelve positions in January 2026 through album-depth streaming, proving British artists can still command attention when the work demands prolonged engagement.

But Dean’s success required full album commitment, not single-song virality. That’s a higher bar than American artists clear.

Lewis Capaldi’s “Survive” became his sixth UK number one in 2025, posting the year’s biggest opening week before Taylor Swift’s “The Fate of Ophelia” overtook it. Capaldi wins individual battles. Americans win the war.

His breakthrough demonstrates British artists can achieve peaks whilst losing the broader chart territory that determines industry power.

Ed Sheeran remains one of few British artists who compete with Americans on streaming scale. “Shape of You” sits at 4.57 billion Spotify streams, second only to The Weeknd’s “Blinding Lights”.

But Sheeran succeeds partly by making music that sounds American-adjacent. His global hits don’t scream “British” the way Arctic Monkeys or The 1975 do. He’s British by passport, international by design.

The 2024-2025 UK chart data reveals American artists capturing over half of Britain’s streaming presence whilst British artists secure less than a third. That gap widened from previous years.

The trend points toward more American dominance, not less. UK charts reflect American dominance that streaming economics favour, and incumbents win. Americans are the incumbents.

When 39th Place Means Failure

Britain ranking 39th for domestic support isn’t just a statistic. It’s a policy failure wrapped in market dynamics disguised as consumer choice.

Cultural policy in France, Germany, and Italy includes domestic content quotas for radio, subsidies for local production, and tax incentives that favour domestic artists.

Britain dismantled those protections in favour of free market competition. The market competition produced American dominance.

Free markets don’t preserve culture. They optimise for profit, and American music industries profit better.

The comparison with South Korea matters. K-pop dominates Korean charts not through accident but through industrial strategy.

Government-backed entertainment companies develop artists with export potential whilst maintaining domestic market presence.

The strategy works because cultural product receives the same industrial policy attention as semiconductors or automobiles. Music becomes too economically important to leave to market whims.

Britain treats music as creative industry that should compete freely. The competition produced Ed Sheeran, Adele, and Dua Lipa at the top whilst hollowing out the middle class of working musicians.

The streaming economics that created 55% American chart dominance also created conditions where fewer British artists can achieve financial sustainability. Concentrating success at the peak accelerates base collapse.

But fixing this requires decisions Britain won’t make. Domestic content quotas? Politically unpalatable. Streaming platform regulations? Technically difficult. Industry subsidies? Fiscally expensive.

The easier path is accepting American dominance as inevitable, which guarantees it becomes permanent. Britain chose to compete in a game Americans designed. The outcome shouldn’t surprise anyone.

Note: This analysis uses data from Skoove’s year-long study of Spotify’s Top 200 charts across 73 countries (May 2024 to July 2025), UK Spotify chart data for January 2026, and industry analysis from multiple sources. Streaming data represents snapshot patterns and should be considered alongside physical sales, live performance revenue, and other music industry metrics for complete market understanding.