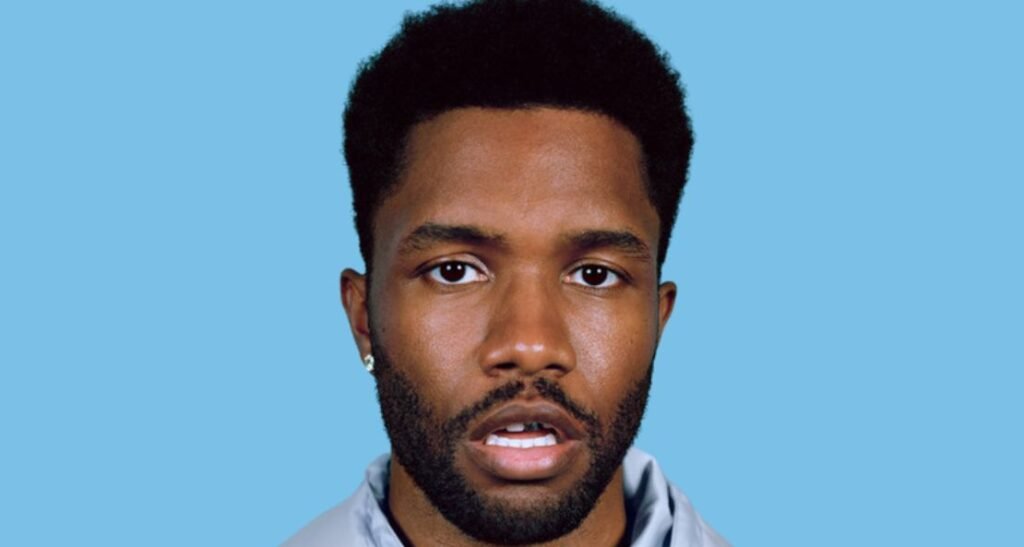

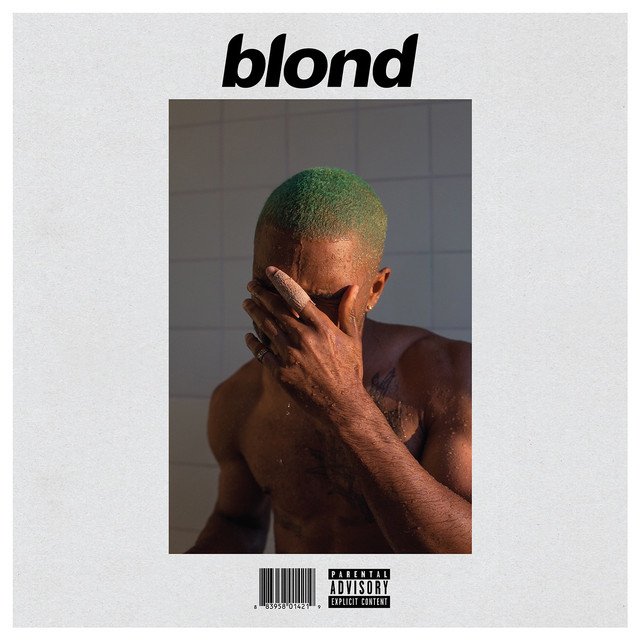

Frank Ocean’s “White Ferrari” stands as one of modern R&B’s most emotionally raw confessions. Released on his 2016 album Blonde, the track chronicles a painful truth: we cannot find lasting peace in other people, only within ourselves.

The white Ferrari serves as a vessel for this realisation, carrying Ocean through memories of a relationship where silence spoke louder than words, where intimacy bred familiarity that ultimately bred distance, and where the search for external validation gave way to hard-won self-acceptance.

The song doesn’t offer easy answers or false comfort. Instead, Ocean maps the exact coordinates of heartbreak, regret, and the moment you stop looking for someone else to complete you.

What Is the Meaning of White Ferrari?

“White Ferrari” tracks Frank Ocean’s journey from seeking peace through romantic connection to finding it within himself.

The song moves through four distinct emotional stages: comfortable intimacy, communication breakdown, acceptance of loss, and philosophical transcendence.

Ocean uses the white Ferrari as a symbol for the purity and fragility of deep connection (white suggesting innocence, Ferrari implying something rare and precious), while simultaneously employing it as a vehicle for memory itself.

The track’s power lies in its specificity. Ocean doesn’t deal in generic heartbreak clichés. He gives us dilated eyes watching clouds float by, the physical sensation of a “slow body,” the desperate post-breakup texts sent at “lesser speeds, Texas speed.”

These concrete details allow listeners to slot their own regrets into his framework, making his personal narrative feel universal.

But the song’s central meaning crystallises in its final movement: “You dream of walls that hold us in prison / It’s just a skull, least that’s what they call it / And we’re free to roam.”

Ocean realises that his partner’s limited worldview (dreaming of walls, feeling small) cannot contain him. The “prison” of their relationship was actually just their own minds.

Freedom comes not from finding the right person, but from refusing to settle for someone who cannot match your vision of what life can be.

Is White Ferrari a Metaphor?

Yes, the white Ferrari functions on multiple metaphorical levels. On the surface, Ocean recounts literal car rides with a past lover.

Cars appear throughout Ocean’s work (see his Boys Don’t Cry magazine essay where he writes, “How much of my life has happened inside of a car?”), and he treats them as spaces where life’s most significant moments unfold.

But the Ferrari represents far more than transport. White symbolises the relationship’s initial purity and innocence, particularly in the “Sweet sixteen” reference.

A Ferrari suggests something rare, valuable, and performance-oriented, but also high-maintenance and easily damaged.

The metaphor extends to the song’s structure: like a Ferrari, the relationship looks beautiful but requires constant, careful handling. When Ocean “forgets to speak,” the engine fails.

The car also works as a metaphor for memory. We “drive through” our past relationships, revisiting moments with the clarity of hindsight.

Ocean positions himself in the driver’s seat (literally and metaphorically), suggesting he had control yet still crashed.

The white Ferrari becomes the vessel for his journey through time, from past to present, from naivety to wisdom.

The Beatles interpolation of “Here, There and Everywhere” (credited to Lennon-McCartney) adds another layer.

Ocean borrows their line “spending each day of the year” to suggest omnipresence, but where the Beatles celebrate constant companionship, Ocean mourns it.

The familiarity that the Beatles found romantic (“running my hands through her hair”), Ocean found stifling.

Why Do People Like White Ferrari by Frank Ocean?

“White Ferrari” resonates because Ocean captures the specific ache of hindsight without drowning in self-pity. The song’s emotional honesty feels almost uncomfortable.

When Ocean sings “You left when I forgot to speak,” he doesn’t make excuses or blame his partner.

He owns his failure to communicate, then immediately shows us the pathetic aftermath: texting what he should have said, driving home alone, haunted by what he couldn’t express in the moment.

The minimalist production (courtesy of Ocean, Jon Brion, and Om’Mas Keith) strips away any defensive layers.

Brion’s orchestration consists mainly of sparse guitar and subtle strings, creating space for Ocean’s voice to sit right in your ear.

This intimacy makes listeners feel like confidants rather than an audience. You’re not watching Ocean’s heartbreak; you’re sitting in the passenger seat experiencing it with him.

The song’s structure defies conventional songwriting. Four verses, no chorus, no hook. This mirrors how we actually process loss: not in neat, repeating patterns, but through fragmented memories that hit us at odd angles.

The pitched vocals in the final verse signal a shift in consciousness, as if Ocean has entered a different dimension of understanding.

Fans also appreciate the song’s refusal to provide closure. Ocean doesn’t get the girl back. He doesn’t claim he’s “better off.” He simply arrives at acceptance: “We’re free to roam.”

This ambiguous ending feels more truthful than the tidy resolutions most love songs offer.

Sometimes relationships end not because someone did something terrible, but because two people want different things from life. That’s harder to process than villainy, and Ocean doesn’t shy away from that difficulty.

You might also like:

- Chamber of Reflection: Mac DeMarco’s Song of Isolation and Self-Discovery

- Ariana Grande’s We Can’t Be Friends (Wait for Your Love): A Symphony of Heartache and Hope

- Neil Diamond Girl, You’ll Be a Woman Soon: The Story Behind the Song

- Unveiling the Heartbeat of Made For Me Muni Long: A Deep Dive into Its Lyrics and Soulful Journey

- The Rise of Tommy Richmans Viral Hit Million Dollar Baby

The Genesis of “White Ferrari”

Frank Ocean assembled an impressive team for “White Ferrari”: himself, Kanye West, Malay, and the legendary Lennon-McCartney partnership (credited for the Beatles interpolation).

Ocean, Jon Brion, and Om’Mas Keith handled production duties, creating the song’s distinctive sonic landscape.

In December 2015, Canadian DJ and producer A-Trak sparked rumours about the track, calling it “the best thing u’ll hear this year.” But fans waited until August 2016 to hear “White Ferrari” in its final form on Blonde.

The wait proved worthwhile. Ocean told The New York Times in 2016: “When I was making the record, there was 50 versions of ‘White Ferrari.’ I have a 15-year-old little brother, and he heard one of the versions, and he’s like, ‘You gotta put that one out, that’s the one.’ And I was like, ‘Naw, that’s not the version,’ because it didn’t give me peace yet.”

That quest for peace defines both the song’s creation and its content. Ocean worked through dozens of versions, searching for the arrangement that would finally bring him closure on whatever relationship inspired the lyrics.

The parallel is striking: just as the song’s narrator cannot find peace in his relationship, Ocean couldn’t find peace in the song until he stripped it down to its emotional core.

Verse-by-Verse Analysis: The Road to Self-Realisation

Verse 1: Comfortable Silence and Youthful Innocence

“Bad luck to talk on these rides / Mind on the road, your dilated eyes watch the clouds float / White Ferrari, had a good time / (Sweet sixteen, how was I supposed to know anything?) / I let you out at Central”

Ocean opens with a paradox: “bad luck to talk.” For two people supposedly in love, silence should feel wrong. But Ocean frames their quietness as superstition, as if speaking would break a spell.

They’re “both so familiar” that words seem unnecessary. This is the comfort stage of intimacy, where you can sit in silence without awkwardness.

But Ocean undercuts this immediately with hindsight: “Sweet sixteen, how was I supposed to know anything?”

The parenthetical delivery (mimicked in the vocal production) marks this as an intrusive thought from the present, interrupting the memory. At sixteen, he mistook comfort for love, familiarity for depth.

The “dilated eyes” suggest his partner was on something, disconnected, and Ocean was too young to recognise the warning signs.

“I let you out at Central” works as both literal (a location) and symbolic. Central implies a middle point, a hub. Ocean drops his partner at the centre while he continues driving, foreshadowing their eventual divergence.

Verse 2: The Failure to Communicate

“I didn’t care to state the plain / Kept my mouth closed / We’re both so familiar / Stick by me, close by me / You were fine, you were fine here / That’s just a slow body / You left when I forgot to speak / So I text the speech, lesser speeds, Texas speed, yes”

Here Ocean admits his fatal error: “I didn’t care to state the plain.” The “plain” truth he should have spoken remains unspoken, but context suggests it’s either “I love you” or “This isn’t working.”

Either way, his silence creates distance. “We’re both so familiar” shifts from comfort to complacency.

The tone changes: “Stick by me, close by me.” Ocean’s begging now, trying to hold on to something already slipping away.

“You were fine here” sounds desperate, like he’s trying to convince both his partner and himself that everything’s okay.

“That’s just a slow body” is one of the song’s most enigmatic lines. It could mean his partner is languid, relaxed, not in a rush to leave.

Or it could reference Ocean’s own slowness to act, his body betraying his mind’s urgency.

“You left when I forgot to speak” lands like a gut punch. The relationship ends not with a fight but with silence.

Ocean’s attempt to fix it (“So I text the speech”) comes too late. “Lesser speeds, Texas speed” suggests both the slow crawl of trying to communicate via text and the vast distance now between them (Texas being synonymous with wide-open spaces).

Verse 3: Acceptance and Enduring Love

“Basic takes its toll on me, ‘ventually, ‘ventually, yes / I care for you still and I will forever / That was my part of the deal, honest / We got so familiar / Spending each day of the year / White Ferrari, good times / In this life (Life), in this life (Life)”

Ocean acknowledges that “basic” (the everyday failures of communication and connection) accumulates over time. “Eventually” (shortened to “‘ventually” in his delivery) these small erosions become insurmountable.

But then comes the song’s most heartbreaking admission: “I care for you still and I will forever / That was my part of the deal, honest.”

Ocean’s love wasn’t conditional on the relationship lasting. He commits to caring regardless of outcome. This isn’t romantic; it’s resigned. He’s accepted that love doesn’t guarantee togetherness.

“We got so familiar” appears again, but now it reads differently. Familiarity bred the contempt (or at least the complacency) that killed them.

The Beatles reference (“Spending each day of the year”) emphasises how much time they shared, making the loss feel heavier.

“In this life, in this life” bridges to the song’s philosophical turn. Ocean’s preparing to zoom out from this specific relationship to larger questions about existence.

Verse 4: Transcendence and Freedom

“One too many years / Some tattooed eyelids on a facelift / Mind over matter is magic, I do magic / If you think about it, it’ll be over in no time / And that’s life / I’m sure we’re taller in another dimension / You say we’re small and not worth the mention / You’re tired of movin’, your body’s achin’ / We could vacay, there’s places to go / Clearly, this isn’t all that there is / Can’t take what’s been given / But we’re so okay here, we’re doing fine / Primal and naked / You dream of walls that hold us in prison / It’s just a skull, least that’s what they call it / And we’re free to roam”

The pitched vocals signal Ocean entering a different headspace. “Tattooed eyelids on a facelift” juxtaposes permanence (tattoos) with attempts to reverse time (facelifts), suggesting the futility of trying to preserve what’s already gone.

“Mind over matter is magic, I do magic” reveals Ocean’s coping mechanism. He can think his way past pain. “If you think about it, it’ll be over in no time” could mean the relationship or life itself. Both are temporary.

The final verse reveals the core incompatibility: Ocean believes “we’re taller in another dimension” while his partner insists “we’re small and not worth the mention.”

This isn’t about physical height. Ocean sees human potential as vast, multidimensional, limitless. His partner sees smallness, insignificance, limitation.

“You’re tired of movin’, your body’s achin'” shows someone who wants to stop, to settle, to accept less. Ocean suggests escape (“We could vacay, there’s places to go”), but his partner can’t or won’t imagine more than “we’re doing fine.”

The song’s thesis crystallises: “You dream of walls that hold us in prison / It’s just a skull, least that’s what they call it / And we’re free to roam.”

Ocean realises the prison is self-imposed. The walls are mental constructs (“It’s just a skull”). We create our own limitations.

The song ends not with reconciliation but with liberation. Ocean chooses freedom over a relationship that would require him to think smaller, want less, be contained.

“We’re free to roam” suggests both physical movement and mental expansion. He’s free of the relationship, free of needing another person to feel complete, free to pursue his own vision of what life can be.

Production and Musical Choices: Creating Emotional Space

Jon Brion’s production work on “White Ferrari” demonstrates restraint rarely heard in contemporary R&B.

The instrumental consists primarily of fingerpicked guitar, subtle bass, and atmospheric strings that swell and recede like breath. This minimalism creates emotional space for Ocean’s voice to exist without competition.

The guitar tone (warm, slightly muffled, intimate) makes the production feel like it’s happening in a small room rather than a studio.

Brion, known for his work on films like Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, brings a cinematic quality that emphasises the song’s visual imagery: clouds floating by, car rides, dilated eyes.

Om’Mas Keith’s contribution shapes the song’s sonic texture. The track’s warmth (unusual for digital production) comes from careful EQ choices that make Ocean’s voice feel physically close to the listener.

Keith’s work on Odd Future and other projects shows his ability to create intimacy through production, and “White Ferrari” might be his masterwork in that regard.

The vocal production deserves particular attention. Ocean’s lead vocal sits just above a whisper through most of the track, occasionally rising to falsetto on emotionally charged words (“close by me”).

The layering is subtle; Ocean rarely stacks many vocal takes, preferring to let individual lines breathe.

The pitched vocals in the final verse mark the song’s only dramatic production shift. Ocean’s voice rises approximately a third, creating an otherworldly quality that signals the narrator entering a new level of consciousness. This isn’t Auto-Tune for effect; it’s a deliberate choice to indicate transcendence.

The Beatles interpolation works musically and thematically. The melody Ocean lifts from “Here, There and Everywhere” brings nostalgic warmth, connecting his narrative to pop music’s long history of documenting love’s complications.

But where the Beatles’ original celebrates omnipresent love, Ocean repurposes the melody to mourn it.

Notably, Ocean created 50 versions before settling on this stripped-down arrangement. Earlier versions presumably featured more instrumentation, more production flourishes, more attempts to make the song “bigger.”

Ocean’s genius was recognising that the song’s power lived in its smallness, its quietness, its refusal to dress up pain in elaborate production.

Cultural Impact: Why “White Ferrari” Endures

Eight years after its release, “White Ferrari” remains a touchstone for discussions about emotional vulnerability in music.

The song’s influence appears in the work of artists like Daniel Caesar, Steve Lacy, and Brent Faiyaz, who’ve adopted Ocean’s model of stripping away production to expose raw feeling.

The track’s impact extends beyond music. “White Ferrari” appears regularly in TikTok videos about heartbreak and self-discovery, in YouTube video essays analysing Ocean’s artistry, and in countless Spotify playlists titled variations of “sad boi hours.”

This ongoing cultural presence eight years later speaks to the song’s emotional accuracy.

Ocean rarely performs “White Ferrari” live, which has only increased its mystique. The studio version stands as the definitive statement, untouched by reinterpretation or evolution.

This preserves the song in amber, keeping it frozen in 2016 while allowing each new generation of listeners to discover it fresh.

The song also sparked academic interest. Music scholars have written about Ocean’s use of automotive metaphors, his subversion of R&B tropes, and his navigation of queer identity through deliberately ambiguous pronouns.

While Ocean never explicitly genders his partner in “White Ferrari,” the song’s place on Blonde (an album that followed his 2012 Tumblr letter about loving a man) invites queer readings that add additional layers to the narrative.

The Journey From External to Internal Peace

“White Ferrari” charts a specific emotional trajectory: from seeking peace in another person to finding it within yourself. This arc defines the song’s movement and meaning.

In the first verse, Ocean looks for peace through connection. The comfortable silence, the shared car ride, the familiar intimacy all suggest someone trying to find rest in relationship. But peace predicated on another person’s presence is inherently unstable.

By the second verse, that peace shatters. Ocean’s inability to communicate destroys what they built. His desperate attempts to recover it (“text the speech”) fail because he’s still looking outward, still trying to fix things through connection rather than introspection.

The third verse shows Ocean accepting loss while maintaining love. This is growth: he can care for someone without needing them to complete him.

“That was my part of the deal” suggests he understands love as something you give rather than something you get.

The final verse achieves transcendence. Ocean stops trying to make the relationship work and starts questioning why he wanted it to.

His partner’s worldview (small, limited, tired) fundamentally conflicts with his own (expansive, limitless, energetic). Ocean realises he cannot and should not shrink himself to fit someone else’s vision.

“We’re free to roam” lands with quiet power because Ocean has stopped equating freedom with being loved.

Freedom means refusing to settle, refusing to accept “we’re doing fine” when you know you could be extraordinary, refusing to let someone else’s walls become your prison.

This journey from external to internal peace mirrors Ocean’s creative process. He made 50 versions of “White Ferrari,” searching for the one that would give him peace.

He found it not by adding more (more production, more lyrics, more explanation) but by stripping away until only truth remained.

The song teaches a difficult lesson: sometimes the most loving thing you can do is leave. Not because the other person is bad, not because you don’t care, but because staying would require both of you to become smaller versions of yourselves.

Ocean chooses expansion over containment, possibility over comfort, freedom over familiarity.

“White Ferrari” resonates because we’ve all faced this choice. We’ve all been in the car, watching clouds float by, knowing we should speak but staying silent.

We’ve all lost someone not through betrayal or cruelty but through the slow erosion of “basic” taking its toll.

And we’ve all had to learn that peace comes not from finding the right person but from refusing to settle for less than we deserve.

Ocean’s genius lies in presenting this realisation without bitterness. He doesn’t blame his partner for being small; he thanks the relationship for showing him his own capacity for largeness.

The white Ferrari carried him to exactly where he needed to go: away from the relationship and toward himself.

Whether you’re a longtime fan or new to his music, the lyrics of White Ferrari offer a journey worth taking.

Frank Ocean White Ferrari Lyrics

Verse 1

Bad luck to talk on these rides

Mind on the road, your dilated eyes watch the clouds float

White Ferrari, had a good time

(Sweet sixteen, how was I supposed to know anything?)

I let you out at Central

I didn’t care to state the plain

Kept my mouth closed

We’re both so familiar

White Ferrari, good times

Verse 2

Stick by me, close by me

You were fine, you were fine here

That’s just a slow body

You left when I forgot to speak

So I text the speech, lesser speeds, Texas speed, yes

Basic takes its toll on me, ‘ventually, ‘ventually, yes

Ahh, on me ‘ventually, ‘ventually, yes

Verse 3

I care for you still and I will forever

That was my part of the deal, honest

We got so familiar

Spending each day of the year

White Ferrari, good times

In this life (Life), in this life (Life)

One too many years

Some tattooed eyelids on a facelift

(Thought you might want to know now)

Mind over matter is magic, I do magic

If you think about it, it’ll be over in no time

And that’s life

(Love)

Verse 4

I’m sure we’re taller in another dimension

You say we’re small and not worth the mention

You’re tired of movin’, your body’s achin’

We could vacay, there’s places to go

Clearly, this isn’t all that there is

Can’t take what’s been given (No way)

But we’re so okay here, we’re doing fine

Primal and naked

You dream of walls that hold us in prison

It’s just a skull, least that’s what they call it

And we’re free to roam