Nicola Bolla’s Van Gogh Chair, a Swarovski‑studded homage to Vincent van Gogh’s 1888 paintings collapsed in June 2025 when a tourist sat on it at Verona’s Palazzo Maffei Casa Museo.

Videos of the crystal‑encrusted seat buckling under a visitor’s weight ricocheted across social media, igniting a global conversation about the delicate line between functional objects and art and prompting viewers to ask why some people feel compelled to touch (and even test) the untouchable.

The incident, soon dubbed the Van Gogh chair fiasco, reveals much about modern consumption of culture; a world where Instagrammable moments sometimes eclipse reverence for craftsmanship.

The chair itself is a work of devotion: Italian artist Nicola Bolla painstakingly coated it with thousands of Swarovski crystals, echoing van Gogh’s colours and textures.

Its allure lies as much in its shimmer as in its fragility. One might expect museum‑goers to treat it with the same hush reserved for a Monet; instead, a couple waited for a guard to leave and began striking poses.

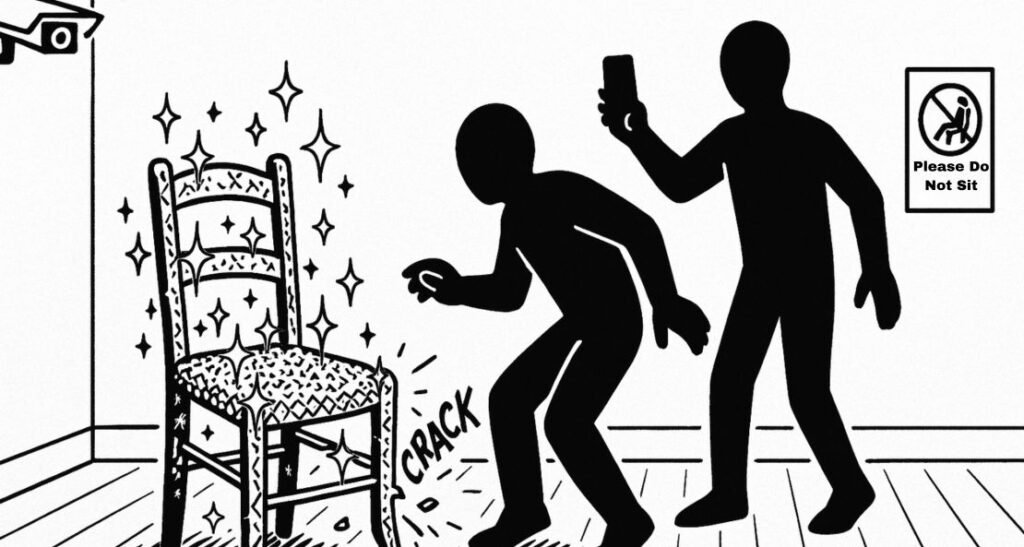

In CCTV footage, the woman pretends to sit for a photo; moments later, her partner lowers his full weight onto the chair and it crumples.

They dash away, leaving behind shards that glisten under gallery lights.

The museum condemned their actions as “superficial” and “disrespectful,” emphasising that they ignored basic rules of respect for art.

Days later, conservators painstakingly restored the chair, but the story lingered.

Viral outrage and the psychology of touch

Online reaction was immediate. “Fire the curator of the exhibit immediately; you didn’t expect a single person to attempt to sit on an open chair?” one Twitter user fumed.

Another noted, “This is why they have to put museum relics behind cages now.” On Reddit, commenters oscillated between disbelief and snarky resignation.

Some blamed the museum for leaving a seat‑shaped object unguarded, while others argued that our selfie‑driven culture encourages risky behaviour in pursuit of likes.

A recurring sentiment was that many visitors see exhibitions as backdrops rather than encounters with painstakingly made works, leading to a sense of entitlement over tactile interaction.

There is also a deeper tension at play: the Van Gogh chair looks like a piece of furniture.

While museums have long displayed chairs (think of Danish modernism or the Eames lounge) as sculpture, those pieces are often exhibited behind ropes or on pedestals, signalling clearly that they are not to be used.

Bolla’s chair sat unencased on the floor, shimmering and inviting, blurring the boundary between object and art.

When an artist takes something as mundane as a seat and transforms it into a jewel‑like spectacle, the result can confuse audiences who are used to interactive displays and immersive experiences.

Chairs as performance art

The Van Gogh chair fiasco is part of a broader movement of chairs becoming performance pieces.

At Milan Design Week 2025, Japanese artist Tokujin Yoshioka unveiled Frozen, a collection of 850‑kg “Aqua Chairs” carved from solid blocks of ice.

The sculptor uses a proprietary slow‑freezing technique to create translucent seats that refract light and gradually melt under exhibition lights.

Yoshioka sees water as a collaborator, allowing time, wind and temperature to shape the work during the show.

He admitted he didn’t know how long his chairs would last, embracing impermanence as part of the design.

As the ice transforms into puddles, visitors witness the chair’s life cycle, a reminder that even solid objects can be fleeting.

Furniture design more broadly has been shifting toward sculptural statements.

Interior trend forecasters note that 2025’s accent chairs are deliberately bold: curved backs, asymmetric lines and innovative shapes turn seats into artistic centrepieces.

Tactile fabrics like bouclé and chenille add depth and softness, while earthy colours (clay reds, olive greens, terracotta) dominate palettes.

Motion features, like swivels or gliders, are hidden within these sculptural forms, making them both functional and performative.

When chairs are designed to provoke conversation, it’s perhaps unsurprising that a museum visitor might see them as interactive props.

Historical echoes and the lure of spectacle

Bolla’s crystal chair draws inspiration from Van Gogh’s Chair paintings of 1888 – humble wooden seats rendered with expressive brushstrokes.

Van Gogh’s interest lay in imbuing ordinary objects with emotion.

By covering his own chair in crystals, Bolla turned that meditation on simplicity into an ostentatious object, a commentary on modern luxury and consumerism.

The chair’s collapse, captured on camera, could be read as an accidental performance piece in itself: an unwitting collaboration between artist and audience that exposes the vulnerability of art.

Such incidents recall other moments when everyday objects doubled as high art.

Marcel Duchamp’s 1917 Fountain repurposed a urinal; the 1960s saw readymades challenge perceptions of utility and aesthetics.

More recently, Swedish artist Anna Uddenberg sparked online debate with her Continental Breakfast Chair, an installation in which a performer is strapped into a contraption inspired by plane seats and hospital straps.

The piece, staged at Meredith Rosen Gallery in New York, critiques passive submission in consumer culture.

Our feature on Uddenberg’s chair delves into how it became a meme and why viewers project their own narratives onto it; a natural companion to the Van Gogh chair story.

Both works harness the familiarity of chairs to interrogate the body’s relationship to power and public spectacle.

Responsibility and repair

The Verona museum has since restored the Van Gogh chair, but the institution faced criticism for failing to protect the piece.

Some argued that placing an unprotected chair in an accessible space invited misuse; others countered that expecting visitors to follow posted rules isn’t unreasonable.

The museum responded with a heartfelt statement thanking police, security staff and restorers for bringing the artwork back to life and emphasising that art must be loved and protected.

Interestingly, there has been no public announcement about whether the couple will be fined or banned; the museum remained focused on promoting respect rather than retribution.

The repair itself becomes part of the narrative, a testament to the fragility and resilience of contemporary art.

What this reveals about us

Why do people sit on art? Psychologists might point to the pleasure of transgression: the thrill of crossing a line, amplified by the possibility of viral fame.

Social platforms reward risky behaviour with attention, and many museums now encourage interaction with installations, blurring expectations.

In the case of the Van Gogh chair, the presence of other interactive exhibits at the museum may have created confusion.

There’s also the matter of interpretive signage, if an artwork is a chair and there’s no barrier, is it reasonable to assume you can sit?

Yet the outrage the fiasco generated suggests that most viewers still instinctively know better.

The reaction on Twitter and Reddit underscores a collective desire to protect the sanctity of art spaces, even as they become more immersive.

One cannot help but compare this to the whispers surrounding Yoshioka’s melting chairs, where visitors watch silently as ice drips into pools, resisting the urge to speed nature along. Respect, it seems, depends on expectation.

Lessons and lingering questions

The Van Gogh chair incident leaves us with open questions. Should museums place stronger barriers around functional objects presented as art, or does that diminish the intended experience?

Are artists partly responsible for guiding viewer behaviour, or is that solely the institution’s role?

When chairs, objects we rely on daily become sculptures, do they inherently invite a different kind of engagement?

And perhaps most provocatively: is an artwork’s vulnerability part of its power?

Bolla’s chair may have broken, but the discourse it sparked endures, reminding us that the line between sitting and seeing is thinner than we might imagine.

As we continue to witness chairs melt in Milan and glisten in Verona, one thing is clear: functional objects are increasingly being used to probe our relationship with consumption, bodies and culture.

If you’re fascinated by how furniture becomes performance art, our deep dive into Anna Uddenberg’s Continental Breakfast Chair explores similar themes and asks whether passivity is a choice or a condition.

The Van Gogh chair fiasco is not just a tale of clumsiness; it’s a mirror held up to a society negotiating the boundaries between art, function, and spectacle.

The next time you encounter a chair in a museum, you might think twice before testing its sturdiness, and perhaps ask why it calls to you at all.

You might also like:

- From Bananas to Breakfast Chairs: The Viral Absurdity of Conceptual Art

- The Continental Breakfast Chair: A Cultural Phenomenon and Artistic Marvel

- The Throne of Pop Art: Decoding the Meaning Behind Claes Oldenburg’s Soft Toilet

- Did Catherine the Great Really Have a Collection of X-Rated Furniture?

- The Curious Case of the Cuck Chair: Internet Slang, Hotel Design, or Something More?