Ten of the top 27 positions on the US Spotify chart belong to songs released before 2010. Fleetwood Mac’s “Dreams” sits at number 10.

Prince’s “Purple Rain” at 14. Radiohead’s “Creep” at 19. The Killers’ “Mr. Brightside” at 20. Kate Bush’s “Running Up That Hill” at 27.

These aren’t novelty revivals. They’re structural dominance.

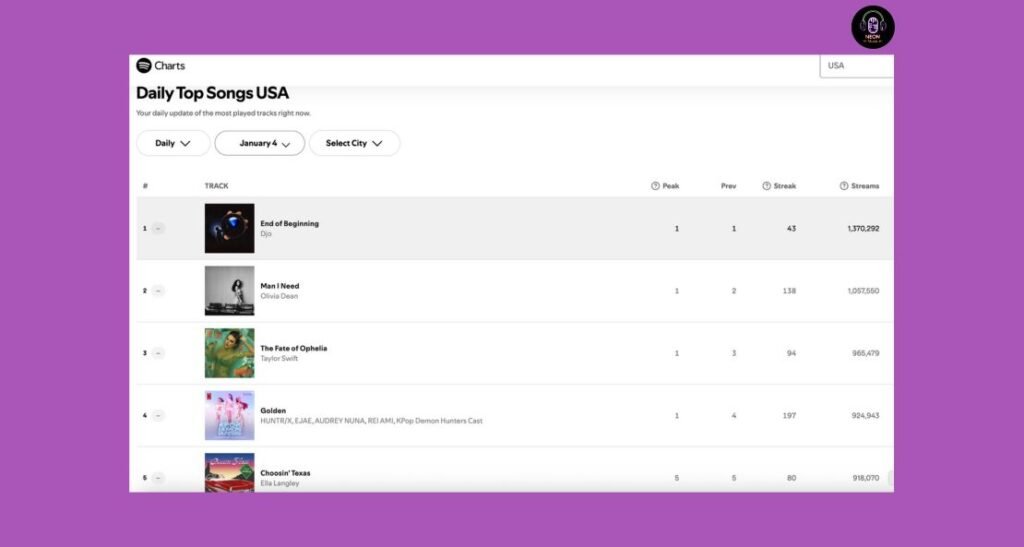

Spotify’s official US daily chart for January 4, 2026 reveals a market where the past outcompetes the present.

Where Japan’s charts demonstrate artist loyalty through contemporary releases and the UK shows album-depth streaming returning for new artists, the US chart operates as emotional archive where proven utility beats novelty.

Catalogue Tracks Occupy Prime Territory

The top 27 US positions contain ten catalogue tracks spanning four decades:

Position 8: “I Thought I Saw Your Face Today” (She & Him, 2010)

Position 10: “Dreams” (Fleetwood Mac, 1977)

Position 14: “Purple Rain” (Prince, 1984)

Position 17: “Landslide” (Fleetwood Mac, 1975)

Position 18: “505” (Arctic Monkeys, 2007)

Position 19: “Creep” (Radiohead, 1992)

Position 20: “Mr. Brightside” (The Killers, 2003)

Position 25: “Every Breath You Take” (The Police, 1983)

Position 26: “Iris” (Goo Goo Dolls, 1998)

Position 27: “Running Up That Hill” (Kate Bush, 1985)

That’s 37% of premium chart real estate held by songs aged 15 to 50 years. This isn’t background streaming.

These tracks occupy positions where new releases typically compete for attention, cultural relevance, and commercial momentum.

The pattern intensifies across the full chart. The Neighbourhood’s “Sweater Weather” (2012) holds position 13.

Fleetwood Mac appears four times total. Arctic Monkeys twice. Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” charts at 136. Across 200 positions, catalogue tracks claim approximately 60-70 placements.

Compare this to the UK chart where catalogue exists but doesn’t dominate top positions, or Japan where catalogue barely registers.

American streaming behaviour in January 2026 reveals audiences preferring emotional certainty over discovery. When you know “Dreams” delivers specific catharsis, why risk a new artist who might not?

The easy explanation would be nostalgia, but that doesn’t hold up. “Purple Rain” works as heartbreak processing, cinematic memory trigger, and communal singalong foundation.

New releases compete against that proven versatility. They usually lose, but not always for the reasons you’d expect.

Sometimes a catalogue track dominates not because it’s emotionally perfect, but because it’s emotionally adequate across enough contexts that nobody complains. Risk mitigation, not risk elimination.

Discovery in US streaming doesn’t mean what Spotify’s algorithms promise. Listeners aren’t finding new artists.

They’re finding that old songs work in new emotional contexts. “Running Up That Hill” didn’t need rediscovering through Stranger Things because it was forgotten.

It needed a Netflix show to give it fresh utility. Americans stream for function, and functional tracks keep working regardless of age.

But here’s where the theory gets messy: if Americans only wanted proven emotional utility, the top 27 would be entirely catalogue. It’s not.

Olivia Dean holds position 2. Taylor Swift sits at 3. The chart reveals audience behaviour somewhere between pure risk aversion and genuine openness.

Maybe the better explanation is that Americans hedge. They stream enough new music to feel engaged with contemporary culture whilst maintaining enough catalogue to guarantee emotional reliability. The split isn’t ideological. It’s practical gambling.

The catalogue tracks don’t cluster by era, either. “Creep” (1992) charts alongside “Mr. Brightside” (2003) alongside “Running Up That Hill” (1985).

The shared utility isn’t generational nostalgia but emotional versatility. Songs that work across contexts win when context itself becomes contested.

Olivia Dean’s Uphill Battle

Dean holds nine US chart positions. In the UK, she commanded twelve. The difference matters, but it understates the challenge.

“Man I Need” peaks at number two in the US. Impressive, until you realise she’s competing for attention against “Dreams” at 10, “Purple Rain” at 14, and “Landslide” at 17.

Her American chart footprint spans positions 2, 6, 33, 54, 80, 120, 131, 139, and 140. Sequential album streaming occurs, but battles catalogue tracks offering decades of proven emotional utility.

Dean’s nine positions represent significant achievement in a market where old songs claim 30-35% of chart territory.

She’s not just competing with Taylor Swift, Morgan Wallen, and contemporary artists. She’s competing with Fleetwood Mac’s entire catalogue, Prince’s legacy, and every emotionally versatile track from the past 50 years.

Which raises an uncomfortable question: if this is what “breakthrough” looks like now, what happens to artists who don’t reach position 2?

The catalogue squeeze doesn’t just make success harder to achieve. It makes failure harder to distinguish from modest success.

What becomes clear is the scale of UK-to-US translation loss. British audiences in January 2026 grant new artists space when the work earns it.

American audiences hedge against disappointment by streaming proven reliability. Cultural trust in artistic curation differs measurably between markets. UK listeners bet on albums. US listeners bet on established emotional utility.

Position 2 suggests Dean can break through catalogue dominance when the song delivers immediately. Nine total positions prove sustained interest exists.

The gap between top and bottom positions suggests Americans sample cautiously rather than commit fully. In a market where “Mr. Brightside” still claims position 20 after 23 years, new artists work harder for less territory.

K-pop’s Measured US Presence

“Golden” by HUNTR/X (fictional K-pop group from Netflix’s “K-pop Demon Hunters” animated film) sits at position 4 in the US. Identical to the UK. In Japan, it placed at 33.

The soundtrack occupies seven US positions: 4, 56, 64, 78, 87, 135, 146. KATSEYE (actual K-pop group) holds three: 22, 40, 147. Jimin’s “Who” climbs to 52, up 26 positions.

K-pop maintains measured presence across all three markets, but the mechanics differ. In Japan, K-pop enters through quality integration rather than fan mobilisation.

In the UK, it storms through coordinated streaming. In the US, it occupies middle positions through sustained moderate engagement.

Position 4 for “Golden” suggests Americans respond to K-pop when packaged as Western media content (Netflix animation) rather than Eastern import.

The fictional groups from an American streaming service chart better than most actual K-pop acts. Cultural translation through Western IP works where direct cultural export sometimes stalls.

KATSEYE represents American K-pop strategy: global members, US-based training, English-language content.

Their three chart positions demonstrate viability without breakthrough. K-pop in America finds audience without transformation. That’s probably sustainable.

You might also like:

- UK Spotify Charts January 2026: Album Streaming Returns

- Japan Spotify Charts 2026: Artist Loyalty Over Playlists

- Spotify Streaming Chart Watch: December 2025 Rankings

- Robyn’s Dopamine Review, Meaning & Video Breakdown

- Lewis Capaldi Drops New EP ‘Survive’

- Taylor Swift’s “The Fate of Ophelia” Lyrics Meaning & Review

Genre Balancing Without Genre Victory

Morgan Wallen appears seven times. Ella Langley three times. Zach Bryan three times. Chris Stapleton three times. Country claims approximately 15-20 positions across the top 200.

Hip-hop through Drake, Kendrick Lamar, Future, Lil Uzi Vert takes similar share. Pop via Taylor Swift, Sabrina Carpenter, Billie Eilish matches. Indie/alternative through Arctic Monkeys, Tame Impala, The Neighbourhood fills remaining gaps.

No genre dominates. Every genre survives. Which sounds like healthy market diversity until you realise it also means nobody’s talking to each other.

This differs fundamentally from historical US chart patterns where single genres (rock in the 1970s, pop in the 1980s, hip-hop in the 2000s) claimed majority positions.

The January 2026 US chart shows genre detente. Streaming algorithms and user choice produce equilibrium rather than dominance.

The mechanism: playlist culture creates genre silos that prevent crossover domination. Country listeners stream country deeply.

Hip-hop audiences stream hip-hop exclusively. Pop fans stick to pop. Algorithms reinforce rather than challenge these preferences.

The chart reflects aggregated segregation, which makes for peaceful coexistence but minimal cultural conversation.

Contrast with UK: British listeners show more genre fluidity. Olivia Dean (pop/soul) coexists with RAYE (R&B) coexists with K-pop coexists with Fleetwood Mac.

Americans compartmentalise more rigidly. The melting pot doesn’t melt anymore. It maintains separate sections.

The Djo Anomaly

“End of Beginning” by Djo sits at number one. A song from 2022 that went viral on TikTok in 2024, maintaining momentum into 2026 through pure emotional utility rather than promotional push.

What Djo proves is streaming’s most profound shift: songs that work keep working. No radio cycle kills them.

No promotion budget determines lifespan. If people return to it, it charts. “End of Beginning” functions as coming-of-age soundtrack, breakup processing aid, and nostalgic comfort simultaneously.

Here’s the absurdity: Djo is Joe Keery, better known for playing a character on Stranger Things than for music.

The number one position reflects functional dominance rather than commercial strategy, which means Americans will stream a three-year-old indie track by someone primarily famous for different work if it accidentally services multiple emotional contexts.

Market maturity looks strange when examined closely. Songs live or die by repeated personal use rather than coordinated cultural moment, which sounds democratic until you remember it also means “Mr. Brightside” never leaves.

For more chart analysis that goes beyond the numbers, subscribe to Neon Music at neonmusic.co.uk.

What Catalogue Dominance Reveals

The US chart doesn’t show what Americans want. It shows what Americans trust. And Americans trust songs they already know work.

Ten catalogue tracks in the top 27 positions aren’t just nostalgia. They’re market conditions where emerging artists face structural disadvantage. Japan’s chart demonstrates cultural cohesion through contemporary artist loyalty.

The UK shows transitional behaviour where albums regain relevance. The US chart reveals mature market risk aversion where proven utility beats novelty.

Which sounds clinical until you consider what this actually looks like for someone launching a music career in 2026.

Your debut single competes with “Dreams.” Your follow-up battles “Purple Rain.” Your third release fights “Mr. Brightside.”

Marketing budgets that once bought visibility now buy temporary interruption of catalogue streaming habits, and the interruption rarely lasts beyond the campaign window.

Artist strategy shifts accordingly. Singles designed for immediate utility testing rather than artistic statement.

Collaborations with established names to borrow their trustworthiness. TikTok virality as the only pathway to “proven” status before official release.

The traditional debut model (unknown artist with strong album) loses viability when audiences retreat to emotional certainty. But maybe this frames the problem backwards.

Maybe the issue isn’t that catalogue dominates, but that we still expect new artists to break through using models designed for markets where old music wasn’t available.

Radio couldn’t play “Dreams” constantly because playlist slots were finite. Streaming has infinite slots, which means “Dreams” never has to leave for Olivia Dean to enter.

The zero-sum assumption doesn’t hold anymore, yet we still evaluate success as if it does.

Genre fragmentation compounds the effect. Country fans stream country deeply. Hip-hop audiences stream hip-hop exclusively. Pop fans stick to pop.

But everyone streams “Dreams” because “Dreams” predates genre segregation. Catalogue tracks bridge divisions new music can’t.

The cost shows in diminished space for emerging artists. Olivia Dean’s nine positions are breakthrough achievement in a market where she competes with 50 years of established emotional utility.

New artists don’t just battle each other anymore. They battle every song that’s ever proven it works across contexts. The bar for “good enough to replace the familiar” keeps rising.

Even breakthrough success requires extended proving periods. Djo at number one took three years to earn trust.

The streaming model promised immediate democratisation: upload today, chart tomorrow. Reality delivers extended probation: upload today, maybe chart in 2028 if it proves reliable enough.

The US chart in January 2026 shows what happens when listeners control outcome completely and choose safety.

You get exactly what you want. You never discover what you didn’t know you needed. And what you want, increasingly, is what you already know works.

Except that framing assumes people know what they’re choosing, and maybe they don’t. Maybe “Dreams” at number 10 represents less conscious risk mitigation and more algorithmic muscle memory.

Spotify queues it after similar tracks. You don’t skip it because it’s fine. It stays in rotation because passive acceptance looks identical to active preference in streaming data.

The chart might reveal not what Americans trust, but what Americans tolerate well enough not to interrupt.

“Purple Rain” at 14 after 42 years isn’t necessarily market maturity choosing proven function. It might just be friction-free background music that nobody objects to strongly enough to remove.

Note: This analysis uses Spotify’s official US daily chart data from January 4, 2026. Chart positions reflect one-day snapshot and may not represent sustained trends. Streaming data should be considered alongside physical sales, radio play, and other consumption metrics for comprehensive market understanding.