There’s something quietly terrifying about a horror film that doesn’t bother to chase you. It just sits there. Watching. Waiting.

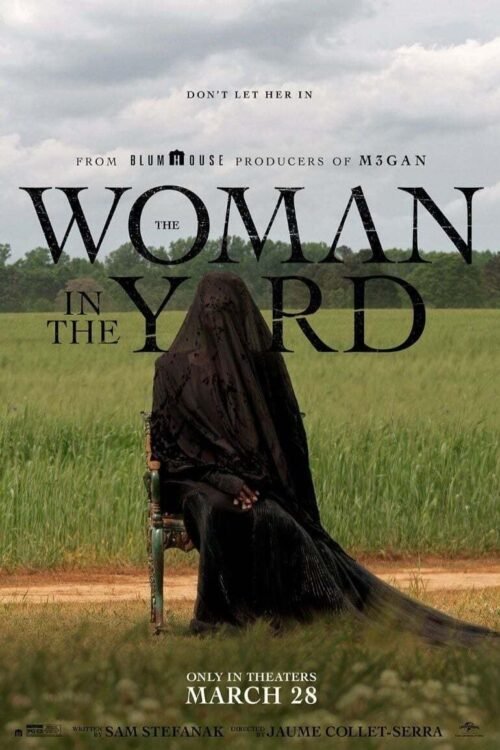

That’s the opening energy of The Woman in the Yard, where a veiled figure appears without a word in the sun-scorched yard of a grieving mother’s farmhouse and refuses to leave.

This image—sunlight, stillness, silence—is disarming. And for a time, so is the film itself.

But what begins with unnerving restraint gradually slips into murky metaphor and narrative overreach, leaving behind a film that’s not broken, just deeply unsure of how much to reveal and when.

The Premise That Promised More Than It Delivered

Director Jaume Collet-Serra (Orphan, The Shallows) returns to horror with a premise that couldn’t be simpler—or more effective.

Ramona (Danielle Deadwyler), recovering from a car crash that killed her husband and left her physically and emotionally fractured, looks out one morning to find a woman cloaked in black lace sitting in her yard. She doesn’t move. She barely speaks. But she’s always there.

The film leans into this minimalism, allowing the dread to accumulate in broad daylight—an unusual but effective choice.

Collet-Serra avoids shadowy hallways in favour of long, sun-drenched takes, as if exposure itself is the threat.

It’s all the more eerie because the Woman (played with otherworldly poise by Okwui Okpokwasili) doesn’t do anything. She just exists. And somehow that’s worse.

But what starts as a bold, quiet horror in the vein of The Babadook or Lake Mungo quickly starts straining under the weight of its own metaphor.

The film wants to say something about mental illness, motherhood, grief, maybe even faith—but never quite gets around to earning those themes.

Danielle Deadwyler Anchors a Film That Won’t Let Her Breathe

Much of what keeps the film from unraveling completely is Danielle Deadwyler. Her performance as Ramona is raw without being showy.

There’s a subtle desperation to the way she limps through her scenes, barely able to keep up with the needs of her children, her home, or herself.

She’s not a traditionally “likeable” protagonist. Ramona lashes out. She lies. She retreats into silence when her kids need her most.

And yet, Deadwyler threads that needle beautifully—she doesn’t play for sympathy, but she earns it anyway.

Opposite her, Okwui Okpokwasili is more presence than person, and that’s by design.

Her veiled figure becomes a kind of visual echo—always there, rarely acknowledged, somehow growing larger just by staying still.

At times, she resembles a symbol more than a character, and that’s precisely where the film begins to falter.

Jaume Collet-Serra’s Vision: Sunlit Terror and Narrative Drift

The first two acts of The Woman in the Yard are masterfully composed. Collet-Serra, aided by cinematographer Pawel Pogorzelski, builds tension through stillness and stark contrast.

The camera lingers just a little too long. Dutch angles skew reality ever so slightly.

And there’s a trick with the Woman’s shadow—an homage to Nosferatu—that lands with an icy chill.

In the film’s production notes, Collet-Serra referenced Carl Jung’s idea of the “shadow self” during production, explaining that the Woman represents the part of ourselves that knows all our secrets and judges us accordingly.

It’s a compelling framework, but the film struggles to fully integrate it into the narrative.

By the third act, what was once precise becomes bloated. The storytelling slips into explanation mode—flashbacks, sudden revelations, metaphysical logic that doesn’t track even within its own rules. The pacing quickens, but the emotion flattens.

The Ending Explained — Metaphor or Misstep?

[Spoilers ahead.]

The Woman, we learn, is a manifestation of Ramona’s suicidal ideation.

She appeared the moment Ramona mentally gave up—shortly before the car crash that killed her husband.

The reveal reframes the entire film as an internal battle between life and death, hope and surrender. It’s Ramona, confronting the version of herself that doesn’t want to go on.

But the metaphor isn’t just told—it’s spelled out. And while that might help casual viewers connect the dots, it undermines the power of the earlier ambiguity.

As Polygon notes, the film rushes its payoff, turning subtext into text before it’s emotionally earned.

There’s also a surreal final image: Ramona reuniting with her kids in a restored version of their home, complete with working lights and a painting of the Woman on the wall—with Ramona’s name written backward beneath it. It’s meant to be haunting. It feels tacked on.

What Could Have Worked: A Stronger Frame for Grief and Guilt

The bones of something meaningful are here. The idea that grief can become an external force—that trauma can haunt not just the mind but the house itself—is well-worn horror territory, but always worth exploring. Where The Woman in the Yard stumbles is in its commitment.

We’re told Ramona has been unraveling for a long time, that her marriage was miserable, that her kids resent her. But these details come too late and too abstract.

As SYFY and Wikipedia confirm, her backstory includes lies about the accident, missed medications, and a desire to escape her own life. But we never sit with that pain—we just hear about it.

The result is a film with emotional ambition but no scaffolding. It tries to collapse into catharsis, but there’s nothing solid underneath to catch it.

Final Verdict — A Film Trapped Between Symbol and Story

The Woman in the Yard is not without merit. It has strong performances, an arresting visual style, and an idea worth exploring.

But it’s a film that mistakes symbolism for substance. It wants to be a psychological horror, a grief study, a twisty supernatural mystery—and ends up being none of them fully.

Still, it lingers. Not because it’s terrifying, but because it brushes up against something real, then flinches. That might not be great horror. But it’s recognisably human.