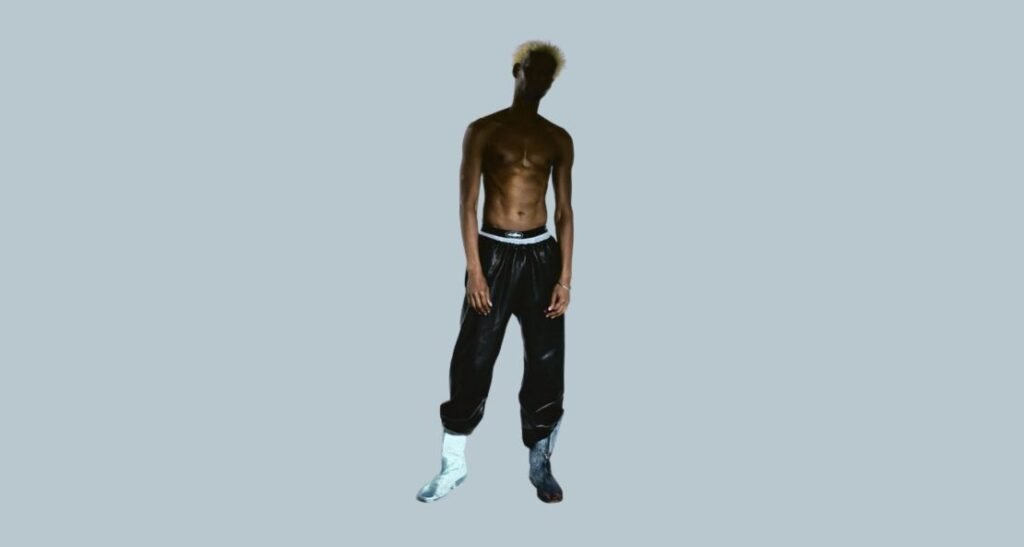

How often do you hear an album that feels genuinely unprecedented? Danny Brown’s Stardust lands like nothing else in hip hop right now.

It is a bold fusion of his Detroit rap roots and the fractured euphoria of hyperpop.

At 44, Brown still carries the wild-vein of his earlier self; nasal yelps, unhinged delivery, lyrics that leapt into bedlam. But Stardust asks a different question: what happens when that chaos meets sobriety?

This is Danny Brown sober, reflective and collaborating with a generation of producers half his age who’ve been raised on SOPHIE, A. G. Cook and the progressive sounds of the internet-underground.

Though its home is Warp Records, the album feels like a hand-over moment; its DNA (hyperpop/digicore underground) recoded by younger producers whose energy pulses under each track.

In a recent interview with NME, Brown made it clear the goal was to “make SOPHIE proud”.

Opening with ‘Book of Daniel’ (featuring Quadeca), the album signals a distinct shift; forgoing playful detachment in favour of an honest, forward-looking stance.

From the first chords and drums you sense a shift: there’s none of the ironic distance that underpinned his earlier work. Instead you hear clean guitar chords, slowly building drums and Brown rapping about growth, legacy and artistic integrity.

When he says, “I am more than a rapper,” it might initially feel like a misstep – as if his emotional range somehow elevates him beyond genre.

But give it time. What he’s really doing is expanding what rap can contain, broadening its emotional spectrum instead of escaping it.

Because that’s what Stardust is. It’s a sobriety album, yes, but it’s also a treatise on flexibility versus rigidity as artists age.

Brown finds himself at a crossroads where many musicians falter: he could have doubled down on the wild persona that made him famous or he could have evolved.

He chose evolution and the music reflects that choice in its hybridity.

“Starburst” kicks things into high gear. Produced by Portuguese DJ Holly (credited on the lead single) the track delivers the squealing synthesiser chaos Brown fans crave.

Also, don’t miss our in-depth feature on how underground sounds like hyperpop, glitchcore and darkwave are reshaping music in 2025 – check it out at Neon Music

But now the lyrics aren’t about substances and excess – they’re ego-driven in a different way, boasting craft rather than consumption.

You hear the reference points: the nerdy, playful touches that show Brown’s cultural range.

In the Frost Children-supplied interlude, Angel Prost delivers a murmured poem about being “drunk with stardust,” a subtle hinge that shifts the conversation from addiction to cosmic surrender in one breath.

That moment reframes addiction not merely as a personal battle, but as a universal force; something odd to hear in Detroit rap, yet entirely in step with Brown’s new vision.

On “Copycats,” with Underscores, Brown interrogates identity through consumption: “Give me that pop star, give me that rock star, give me that rap star.”

The repetition hammers home how we define people by what they consume rather than who they are.

The lyric meaning here cuts deep when you consider Brown’s journey: moving away from defining himself through consumption (drugs, alcohol, sex) toward creation and connection.

Then “1999” arrives (produced by Johnnascus) and the tone gets nerdy as hell. Brown raps about Kangol hats, zoot suit riots and the theory that the world ended in 1999 and we’re all trapped in a simulation.

“We glitch in, no fixing, we are dead inside.” It’s Gen X disaffection meeting millennial irony, but Brown pushes past both toward something more sincere.

The beat breaks into shards of static and shards of funk; something more like a distressed arcade circuit than a conventional hip-hop groove.

“Flowers,” featuring 8485, flips into full 80s-inflected hyperpop mode: discordant robot-punch sounds that should not work but do. Brown’s verse about dandelions in his brain feels psychedelic without substances, which is the entire point. The aggression that’s always been there is just redirected.

“Lift You Up” might be the album’s centrepiece. Beneath a house-leaning beat (one of Holly’s contributions) Brown reflects on being an underdog, on comeback narratives, on gratitude: “Someone else’s shine doesn’t make you dull.”

It’s advice for younger listeners and a reminder to himself. The track properly showcases electronic dance music’s Detroit roots, which matter when discussing this album’s hybrid sound.

EDM and house came out of the same post-industrial Black Midwestern conditions that birthed hip hop. Brown is not borrowing – he is reclaiming.

What makes these collaborations work is mutual understanding. Brown gets the aesthetic: the earnestness, gender-fluidity, progressive politics of the younger scene.

And these younger producers understand where he comes from, what Detroit rap means, what it took for him to get here.

That analogy holds on both sides, which is why tracks like “What You See” (with Quadeca) and “All4U” (with Jane Remover) feel cohesive rather than forced.

“What You See” addresses the shame that comes with addiction head-on. “What do you see in me?” is not just romantic vulnerability – it’s someone who has felt unlovable asking why anyone would stick around.

Brown traces his own misogyny back to heartbreak, to attitudes he learnt implicitly. The self-awareness is uncomfortable and necessary.

The Underscores-produced “Baby” takes things in a playful direction, a tongue-in-cheek hyperpop love song.

While not a cover of Justin Bieber’s track, it nods to pop tropes through a hyperpop lens.

One track that stands out for its brisk intensity is “Whatever the Case” (featuring IssBrokie).

Its frenetic production and clipped lyrical delivery reinforce the album’s thrust toward reinvention.

At just over two minutes, it acts almost like a relay sprint before the album pivots into more expansive, introspective territory; a moment of pure hyper-rap urgency within the broader sober reflection of Stardust.

Then “1L0V3MYL1F3!” with Femtanyl builds around jungle beats and the Amen break, opening into this gorgeous, expansive chorus: “Never take this shit for granted / Sound like run the planet.” Brown is right on the nose: zero irony, just gratitude.

“Right From Wrong” (featuring Nnamdï) continues the spiritual thread.

Brown preaches here with a preacher’s cadence about understanding what matters versus what does not: “The shame of not knowing right from wrong, of feeling like a psychopath when you’re just lost.” That is addiction speaking and Brown calls it out directly.

By the time you reach “All4U,” with Jane Remover, the album’s thesis crystallises. Is Brown talking about making it as a rapper or making it through sobriety? Both.

It becomes dialectical: “This rap shit saved my life” becomes literal. Music filled the hole that consumption never could.

The Polish-language vocals (credited to Ta Ukrainka) on “The End” add another layer: looking at childhood photos, feeling distant from that person you used to be. Every addict knows that feeling – the self you before the disease took hold.

What stands out on Stardust is the sheer absence of detachment; Brown meets his material head-on, in full sincerity.

This is a millennial-rapper (someone raised on edge-lord humour and disaffected coolness) choosing earnestness at every turn.

No cynicism, no sarcasm, no hiding behind personas beyond the occasional stylistic aggression.

Just Danny Brown being vulnerable about recovery, relationships and the saving grace of hip hop itself.

From house pulses to neuro-glitch breaks, the production on Stardust pulls off a rare feat: pushing at the fringes while staying inviting.

Holly, Underscores, Jane Remover and Quadeca all dial into Brown’s voice and message, not the other way around.

These are not just hyperpop beats with rap slapped over them; they are tailored for his voice and what he is trying to say.

Does every track land perfectly? Some lyrics get extremely explicit, particularly around sex, which will not be for everyone.

What Brown has ultimately created here is a model for how hip-hop artists can age without calcifying.

He is not clinging to past glory or chasing earlier success. He is growing, adapting, staying flexible rather than rigid.

The opposite of weakness is not strength; it is flexibility, because age takes strength but you can always learn to stretch.

Stardust stands alongside recent growth albums as proof that rap can contain vulnerability, broad self-examination and genre-defiance.

The genre’s emotional range expands not because artists are becoming “more than rappers,” but because they are showing what rap always could contain.

For anyone struggling with addiction or knowing someone who is, this album offers something genuine: not solutions, but solidarity.

Brown is not preaching from a position of having figured everything out – he is documenting the process, the daily work, the gratitude that replaces consumption.

The final track’s ambiguity, “Didn’t know I could make it here,” works as both artistic and personal triumph.

Brown has made it to sobriety and into this strange new sound world simultaneously, and neither was guaranteed.

The music itself becomes his higher power, his reason to stay clean, his contribution to the world.

This is Danny Brown at his most vulnerable and paradoxically his most confident. Stardust does not sound like any other hip-hop record this year and it does not sound like hyperpop either. It is something truly hybrid, truly new, genuinely moving.