You’ve seen death wear a cloak, ride a horse, whisper in riddles, or light a cigarette before taking someone’s soul.

Sometimes it knocks. Sometimes it just watches. But it always shows up — not just in real life, but in the songs we hum and the movies we can’t look away from.

Why do artists keep giving death a face, a voice, a sense of style? And why does it feel… comforting, even when it shouldn’t?

This isn’t about jump scares or tragic endings. It’s about how we’ve turned the unknowable into a character we can sing about, laugh at, or challenge to a chess match.

Once you notice how often it happens, you might start to wonder what that says about us. About fear, about memory, and about how we cope with the one thing we all eventually face.

Death with a Voice

In film, death is rarely silent. Take Final Destination’s William Bludworth (played by Tony Todd). He doesn’t kill — he explains. He doesn’t chase — he observes.

But there’s something unmistakably final in the way he speaks. Like he knows exactly when your time runs out, but won’t say it out loud.

Then there’s Meet Joe Black, where Brad Pitt’s Death isn’t cold or cruel. He’s curious. He borrows a body to learn about life, love, and peanut butter.

It’s disarming, how gentle he is — which makes the weight he carries feel heavier.

Death in these films isn’t just a plot device. It’s a presence. And once it starts talking, you can’t stop listening.

Death in Lyrics

Music doesn’t need visuals to make death feel real. Sometimes all it takes is a whisper in the dark.

In Billie Eilish’s “bury a friend,” death breathes down your neck. In Bob Dylan’s “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” it feels like a shoulder being tapped one last time.

Metal turns death into a deity. Folk turns it into folklore. And gospel makes it feel like something you meet at the end of a long, dusty road.

Nick Cave practically invites death in like an old friend — offering a drink and a dirge. And in murder ballads, death often arrives before the chorus finishes. You know it’s coming, but you listen anyway.

From a psychological perspective, this recurring motif might connect to Terror Management Theory — the idea that reminders of mortality drive us to seek meaning, comfort, or control.

In this case, personifying death helps transform the unbearable into the narratable.

When Death Becomes Desirable

Not every portrayal of death is drenched in dread. Sometimes, it’s welcomed. Romanticised. Even longed for.

Think of Lana Del Rey’s languid daydreams or the soft fatalism in The Smiths’ lyrics.

In “There Is a Light That Never Goes Out,” death is framed as a perfect, poetic ending: “To die by your side is such a heavenly way to die.” It’s not just drama — it’s desire folded into despair.

In films like The Lovely Bones and Ghost, death becomes part of the love story. It doesn’t end connection; it reframes it.

The afterlife isn’t a void — it’s a continuation. A version of comfort, even if unreachable.

The Evolution of a Character

Over time, death’s wardrobe has changed. The scythe and cloak of early cinema gave way to teenage sarcasm, digital erasure, and minimalist metaphors.

In the 1930s, death moved slowly. It loomed. In the 1990s, death arrived with irony — think Scream and Final Destination, where it played by rules but never showed its face.

Today, death might be algorithmic, ambient, or played by someone conventionally attractive.

The more we modernise it, the more it adapts — slipping into whatever shape makes us stop scrolling.

Streaming, Stylised, and Still Watching

In the streaming era, death has become more fluid — visually, thematically, even technologically.

In Black Mirror, it isn’t a figure at the end of life. It’s a glitch in a backup file. A digital afterimage. A consciousness that keeps responding to texts long after the body is gone.

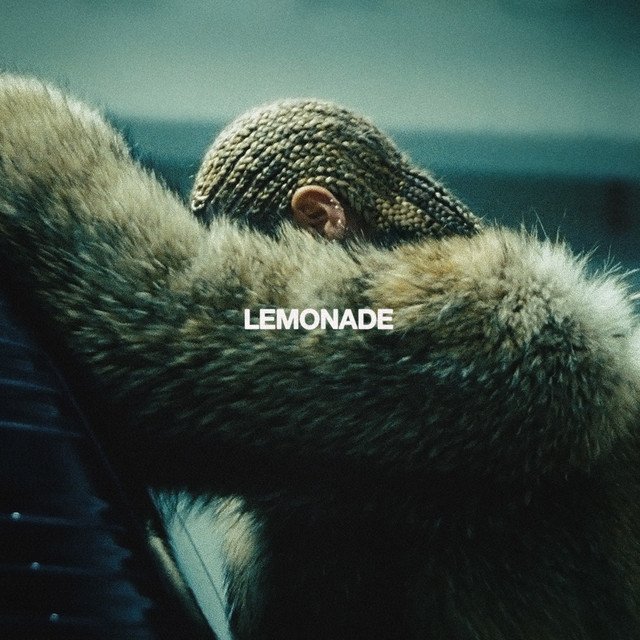

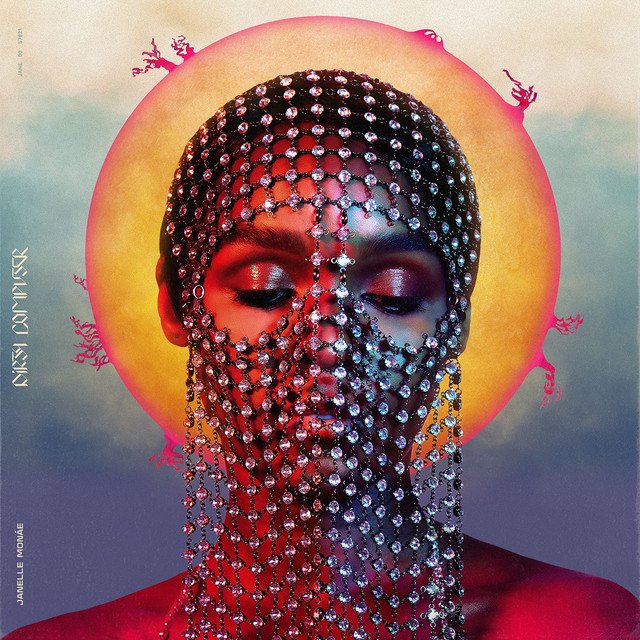

Visual albums like Lemonade and Dirty Computer use death not as an endpoint, but as metaphor for transformation.

In Lemonade, Beyoncé moves through the emotional death of betrayal — mourning a version of love, identity, and self before re-emerging.

The album walks through grief like it’s a room you decorate, rearrange, then leave behind. By the time she reaches “Formation,” the version of herself that entered the album is already gone.

In Dirty Computer, Janelle Monáe’s death is systemic. It’s what happens when individuality is scrubbed clean.

The “dirty” label marks those society wants to erase — queerness, Blackness, rebellion. In this world, death is erasure. And the resistance? Remembering. Reclaiming. Singing louder.

Both projects blur the lines between dying and evolving — offering death not as absence, but as shedding. What dies isn’t the person. It’s the version they no longer want to carry.

The Point of Personification

So why give death a personality? Because it’s easier to talk to something with a face. Easier to imagine, easier to challenge.

If death can be tricked, reasoned with, or seduced, then maybe it’s not entirely in control. Maybe we still have a say.

Personified death becomes part of the emotional landscape — not just the event at the end.

It can even be funny. In The Seventh Seal, death plays chess. In Discworld, DEATH has a dry wit and a horse named Binky. These portrayals don’t erase the fear. They make space for it.

And while personifying death is common in many Western narratives, it’s worth noting that not all cultures do this.

In some Eastern philosophies, death is not an entity but a process — something cyclical and inseparable from life.

In those cases, personification might even feel reductive, unnecessary, or irrelevant.

Which only highlights how much our own portrayals say more about us than death itself.

Why We Keep Doing It

Because what else are we supposed to do? We write about what we don’t understand. And death — no matter how many charts or rituals or songs we make — remains the biggest question mark.

So we draw it with hollow eyes or soft smiles. We give it capes or jokes or a playlist.

We turn it into someone with good posture or a bad attitude — someone worth writing about.

And somewhere between the melody and the metaphor, we convince ourselves that if death ever does come knocking, at least it’ll have the decency to introduce itself.

Want more? See how Final Destination builds an entire franchise around the rules of death in our full trailer reaction to Final Destination: Bloodlines.