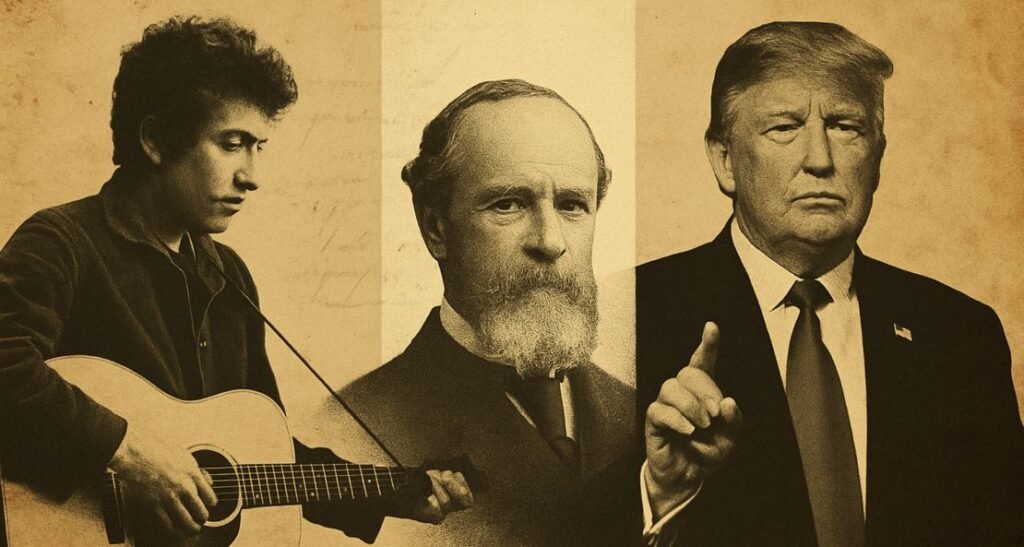

Bob Dylan exploded on the music scene in the early 1960s. Songs like “The Times They Are A’Changin’” (1964) expressed what many were feeling.

The biopic A Complete Unknown (James Mangold, Director, 2024) captures the man and the mood and unintentionally previews the way times are a’changing these days, despite dramatic differences in the two eras.

Timothée Chalamet plays Dylan in the early 60s, with the story focused on his emergence from obscurity to fame.

True to the singer’s riveting personality, the actor plays him bold, dramatic, and ready to follow his own impulses wherever they would lead. So far, that sounds like Donald Trump.

To compare Dylan and Trump may sound irreverent to their very different supporters or may bring a welcome “coolifying” pop culture boost for the conservative president.

Neither is the point here. The very different messages of these phenoms readily show their contrasts. Yet they resemble each other in style.

They are both outstanding performers, each with a commanding personal presence and each with magnetic power to attract or repel their audiences.

Those similar qualities can shed light on political and cultural trends since the 1960s. Politicians and commentators ignore this power at their peril.

In politics, the unpredictable Trump brings to mind the “madman” approach to leadership honed by Charles De Gaulle in France and by Richard Nixon in the US; they hoped to gain political advantage by leaving people wondering what they would do; or what wouldn’t they dare?

The “complete unknown” singer didn’t engage in politics, as madman or otherwise, but he has remained mysterious, leaving people guessing.

True to his public persona, the movie Dylan only smiles twice, briefly (The Times They Are A-Changin’ album [New York: Columbia Records, 1964].

In defiance against charges that he attempted to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election in Georgia, Trump looks deadly serious (Fulton County, GA, Sheriff’s Office, January 2021.

Donald Trump Mugshot Megathread

byu/tragopanic inpics

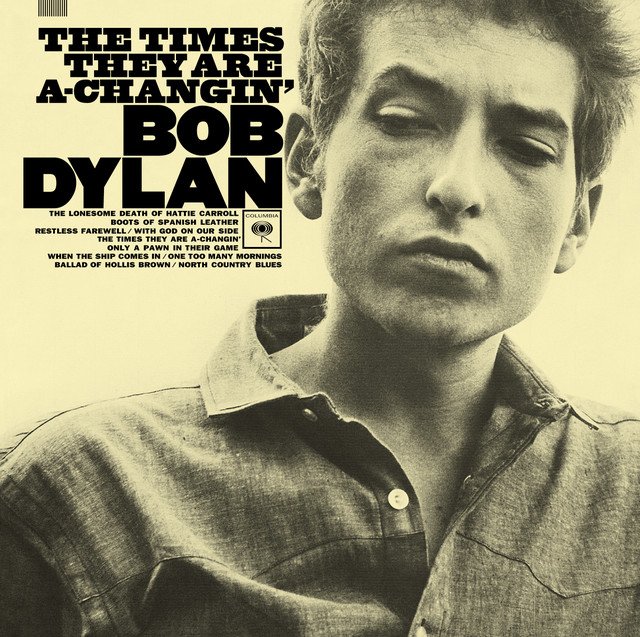

Dylan and Trump each show an ability to persuade not with reason, but as American psychologist William James would say, by appealing to the sentiments of their audiences.

Dylan: It Ain’t Me You’re Lookin’ For

Remaining only partially known, the brilliant singer was ready to follow his own creative sparks.

As Dylan said in 1964, “I want to write from inside me,” no matter what others thought.

That commitment to personal expression was a big part of the ‘60s. So too was striving for peace and social justice.

But Dylan insisted, “I’m not part of no movement.” Trump too didn’t join existing movements but readily turned his campaigns into movements for his own brand of politics.

Dylan drew on the impulses of movement advocacy for his creativity.

That launched his appeal to folk musicians who had made a tradition of advocacy for a better world, and the movie shows him with three famous folk singers.

Dylan pays homage to Woodie Guthrie. He sang and coupled with Joan Baez. And Pete Seeger supported Dylan’s takeoff.

Seeger uses the image of a seesaw to explain Dylan’s relation to folk music advocacy.

The largely indifferent mainstream sat on one side as if weighed down by bricks, ignoring calls for peace and justice.

On the other side, with their advocacy, folk singers like him added a little sand at a time. By contrast, Dylan brought a shovel.

Was Dylan good for the messages of folk singers or not? First, he delivered stern warnings from the heart to change agents: if they “can’t conceive of how others hurt…. I don’t think they’ll give birth to anything.”

And because Dylan was channeling those transformational impulses for his creative purposes rather than immersing himself in them, he was ready to move on to other creative sparks, including electronic music and rock music, on the path to popular fame.

This tension came to a head at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, as Elijah Wald chronicles in Dylan Goes Electric!

Powered by electronic sounds, he belted out his new rock music hit, “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Sorting out this new Dylan, the audience split, some cheered him, and some booed.

His sheer popularity boosted attention to folk music causes, even as his appeal was in such a different key.

Nina Silber points out that this split was a chapter in the challenges reformers faced trying to gain support for progressive causes, especially for opposition to the widening American war in Vietnam.

Dylan danced with the “paraphernalia of fame,” as Silber quotes her own father, Irwin Silber, co-founder of Sing Out! magazine, “the go-to magazine for countless folkies,” as his daughter reports.

The emerging icon followed his own creative muse no matter where it would lead, including his celebrity status.

His persona leaned toward ignoring or even dismissing fame. But that scornful stance was both an expression of his spark and part of his popularity.

In 1965, he said, “I’m a trapeze artist.” He performed as an unknowable genius, which was also part of his creativity.

When composing “Like a Rolling Stone,” he felt a “ghost picked me to write the song.”

Whether the spectral Dylan enlisted his creative daemon or made an artful grasp at mass popularity, he acted in ways difficult to understand but easy for lots to love, with the singer not looking back on those not cheering.

Trump: Times A’Changing

Donald Trump rose to fame in real estate, at glitzy parties, and with appearances in movies, and in 1988, on The Oprah Winfrey Show, toying with a run for president.

He said, “I would never want to rule it out totally.” He parlayed his performer persona as master of “the art of the deal” into a role as the brash TV boss scrutinizing guests to choose as “The Apprentice” in his business ventures.

With no political experience but with celebrity status, he stepped into politics with apparently outlandish claims that Barack Obama was not born in the US.

This type of statement would become his political brand, so bold that the shock alone would gain him wide attention.

Analyses by professionals and intellectuals disproving the facts of his claims have actually added to his popularity as a tribune of those out of power against the elites.

Decades of the rich growing richer and more influential have been increasing the frustrations of those left behind.

Even though Trump himself is an elite figure, many average citizens rally behind him as “our elite” in the contests of the powerful.

Peter Turchin refers to Trump as an example of a “counter-elite,” with a display of righteous strength enabling him to embody the resentments of millions, just as Dylan spoke for many about the mood of his time.

Trump’s persona of toughness had already gained him wide popularity when he announced, with dramatic descent from an escalator height, in June 2015, that he was running for president.

Many among his followers have been willing to give him a pass for straying from truths because his expressions of their experiences have felt so compelling to them.

This has enabled him to approach political talk as artistic production, even as each dramatic statement has definite policy implications.

His supporters readily call his sweeping, if inaccurate, comments spotlights on issues ignored by the powerful.

Corrections by his detractors with fact-checking do not feel as real as the experiences he gives voice to.

Meanwhile, his general comments keep everyone guessing on what will emerge from his impulsive thinking.

As a politician with few ideological commitments, Trump’s style is at the heart of his politics.

Like Dylan, Trump follows his inner drummer, with confidence adding to his appeal. And like Dylan, Trump has split his audience.

His supporters show avid trust even as approximately the same number of Americans have been appalled by the way he has sought concentrations of power and threatened vengeance against all he calls his enemies.

He faces controversies in legal charges and court challenges for his attempts to shape government, and his approval ratings are down, but he maintains support from about half the country.

Trump polarizes his audiences, with stakes still higher than when Dylan alienated half his listeners.

In his March 6 Speech to Congress, the president lamented that “there is absolutely nothing I can say to make [Democrats] happy.” By July 4, he amplified his animosity, saying about the opposition party, “I hate them. I cannot stand them.” Trump is also not looking back at those who are not cheering.

James: Beyond the Mongrel Dogs who Teach

Dylan might want to take “a soldier’s stance, …aim[ing his] hand” at intellectual James, even as the psychologist provides clues about the heart appeal of both charismatic leaders.

The founder of American psychology evaluates the origins of our thoughts, from philosophies to hunches, in the sentiments of each person’s rationality.

Feelings, traditions, interests, and tastes provide “at home” assumptions that make those first steps attractive or even seem like the only reasonable way to think.

Dylan and Trump, like everyone else, have their own sentiments and their own outlooks.

Their talent has been for the expression of their views in ways that resonate with a whole lot of people.

Part of their appeal is like that of many leaders. They read the mood of their time. They express in tune with it. They present in persuasive ways.

And they add an ability to be contrary, to say or do things outside of norms, until other people line up in their support.

In fact, on holding their ground, their very forms of difference become their distinctives. As James puts it, “the most novel” statement seizes attention.

With their audiences either craving or disliking them, the iconic singer and the polarizing politician gain attention by addressing people in their hearts.

Without trying to be conventionally “good,” Dylan’s raspy voice made his words sound all the more honest.

Similarly, Trump’s defiance of elites has encouraged his followers to think of him as speaking truth to power, or even channeling higher powers.

The uncanny similarities of Dylan and Trump show how conservatives have often pulled 1960s messages toward their own purposes, for example, on liberal concern for minorities.

Conservatives have presented themselves as minorities, accusing liberals of discrimination against them. It’s a difficult argument for liberals to manage.

Comparing Trump and Dylan shows a conservative using the irreverent style of the 1960s as a vehicle for his conservative claims.

Dylan has remained irreverent, tapping many musical standards but with virtually no overt political expression, and following his own drummer, now with well over 50 albums.

Commencement: Can This Really Be the End?

Politicians of both parties need to reckon with the passions in politics forecast by Dylan and manifesting in Trump.

Having found their rock star, Republicans may decide to bask in his glow, letting Trump’s brash style touch the hearts of half the country while the other half gags.

The first months of 2025 have shown Administrative and Congressional Republicans using their base of support to make structural changes in tune with decades of conservative hopes.

But hitching their wagon to the star of Trump’s style presents a risk.

For example, his rollout of tariffs has been confusing, with multiple rationales offered and many swift changes. Signs of chaos?

Or maybe just confusion by plan in reflection of his long-standing ways to keep people guessing, or to seize attention.

If his promises for increased manufacturing come true, Trump could benefit from defying experts predicting inflation and recession.

But if those predictions prove correct, the president and party will be blamed.

Democrats out of power face complicated choices but significant opportunities.

Can they better improve their standing with advocacy or with persuasion?

Finding candidates to serve as equal-and-opposite Trumps would offer a kind of counter advocacy.

Perhaps their own boldness would sway voters. Yet this could lead to a political arms race with increasingly lurid charges back and forth.

And voters might actually prefer The Donald over an imitation. Plus advocacy can inhibit persuasion.

Politicians would do well to follow Dylan’s words, suggesting they will become their own “enemy in the instant that [they] preach.”

Democrats advocating can affirm their existing voters, but with little hope for gaining wider support.

However, an understanding of the riveting appeals of Dylan and Trump offers first steps in gaining support from those audiences.

Democrats could identify points that go to the heart of Trump’s heartfelt appeal, especially resentment against elites, and ask average citizens: Is “your elite,” who claims to be your spokesman, really working for you?

If Democrats listen to their voters, they could present alternatives addressing those feelings, but with attention to their own policies.

James calls this “putting yourself at the other fellow’s point, then moving the point and him following.”

Trump voters, first stirred to resentment of elites, but newly alienated by cuts to Medicaid or disaster relief, might direct their heartfelt anger toward Trump himself.

Democrats would be best able to rise to that populist surge if they reduced their own ties with elites.

With the music and style of Bob Dylan providing previews about the challenges of appealing to people’s hearts, the choices of the parties will shape whether the politics of the future will be in the style of two-term Donald Trump or whether he becomes a two-hit wonder.

Paul Croce is the author of two books, most recently Young William James Thinking (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018); author interview. He taught history at Stetson University from 1988 to 2024 and directed the American Studies Program. With retirement, he is applying his teaching and James’s insights to The Public Classroom, a platform for bridging the academic world and public life and for listening across differences.