The voice sounds different here. On Stick Season there was control to it, something considered and even.

On “The Great Divide” that control loosens earlier than you expect, before the song has given him a reason to let it.

He’s been sitting on this one since at least 2024, when he debuted it at Fenway Park to 38,000 people who didn’t know the words yet and sang back anyway.

The studio version, produced by Gabe Simon and Kahan himself, landed January 30, 2026, and in its first week pulled 19.3 million U.S. streams and debuted at No. 6 on the Billboard Hot 100. It became his first No. 1 on the Hot Rock & Alternative Songs chart after two previous No. 2 finishes.

For an artist whose previous era was defined by communal catharsis, this is his first major release built around personal accountability instead.

None of that explains what the song actually does.

What “The Great Divide” Is About

“The Great Divide” is about the guilt of realising, too late, that someone you loved was suffering in plain sight.

Kahan is reckoning with a friendship he watched silently collapse; a person quietly drowning in depression, religious trauma, and what the lyrics suggest was suicidal ideation, while he stared ahead like everything was fine. He thought he knew this person. He hadn’t asked nearly enough questions.

The chorus makes the guilt concrete:

“You know I think about you all the time / And my deep misunderstanding of your life.”

Years of silence compressed into a line. Not nostalgia. Admission.

The Sound

It runs five minutes. A banjo opens it with something almost jaunty before the guitar comes in and the weight of the thing becomes clear.

The band holds back through the verses, then doesn’t, and the distance between those two states is where the song does its work.

The final third drops the lyric entirely. An extended instrumental that builds without resolving.

Multiple listeners reached for Sam Fender as a reference point; there’s something in the scale of it, the way it pushes toward something communal without quite getting there, that earns the comparison.

But where Fender’s crescendos often feel like release, this one feels like endurance.

Gabe Simon produced this track, not Aaron Dessner. Dessner is involved with the broader album but not here, despite the opening guitar figure drawing that comparison from listeners. The ear isn’t wrong. The credit is.

The vocal across the chorus is the best of his career so far. He doesn’t hit the chorus. He pays for it.

The Lyrics

The first verse sets the relationship without softening it.

“We got cigarette burns in the same side of our hands / We ain’t friends / We’re just morons who broke skin in the same spot.”

Trauma-bonding disguised as friendship. Two people drawn together through shared self-destruction rather than anything they’d recognise as closeness.

Then:

“But I’ve never seen you take a turn that wide / And I’m high enough to still care if I die.”

One of the most precise lines he’s written. The recklessness of youth captured in a dependent clause. He tried to read the thoughts his friend had worked overtime to suppress. Got told to back off. Said nothing for a while.

Verse two is where the full weight arrives.

“And how bad it must have been for you back then / And how hard it was to keep it all inside.”

He understands now what he didn’t understand then.

The chorus that follows is shaped like hope:

“I hope you settle down, I hope you marry rich / I hope you’re scared of only ordinary shit.”

But the payoff line inverts it. The wish is that his friend’s fear has shifted from something theological and existential to something manageable. Murderers and ghosts. Not the soul. Not what He might do with it.

The religious dimension of the song is deliberate. The subject was caught between depression and faith in a way that made both heavier. Wanting to disappear but afraid of where disappearing might lead.

The bridge confirms it without spelling it out:

“Did you wish that I could know / That you’d fade to some place / I wasn’t brave enough to go?”

Brave enough to go. That’s the line that separates observer from subject. He didn’t miss it. He misread it.

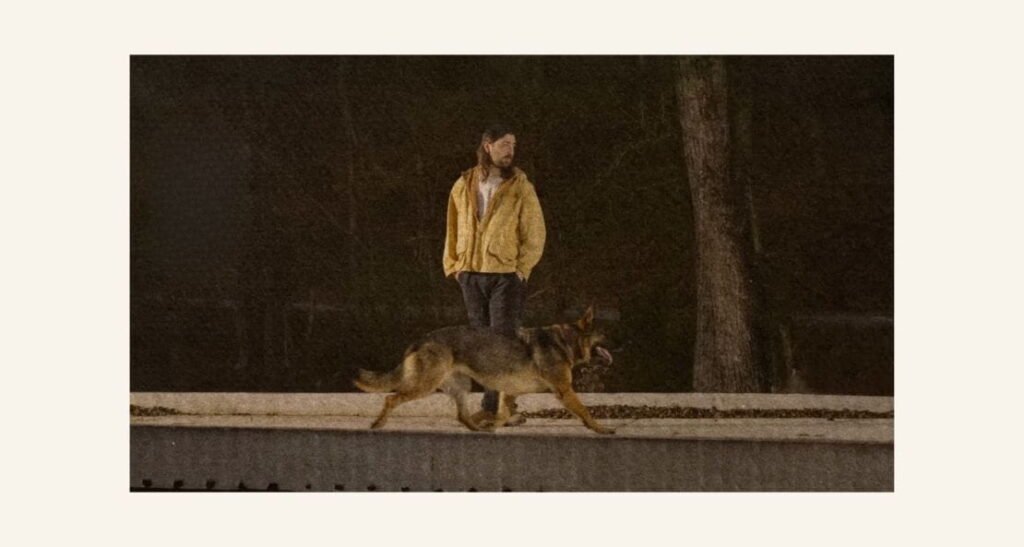

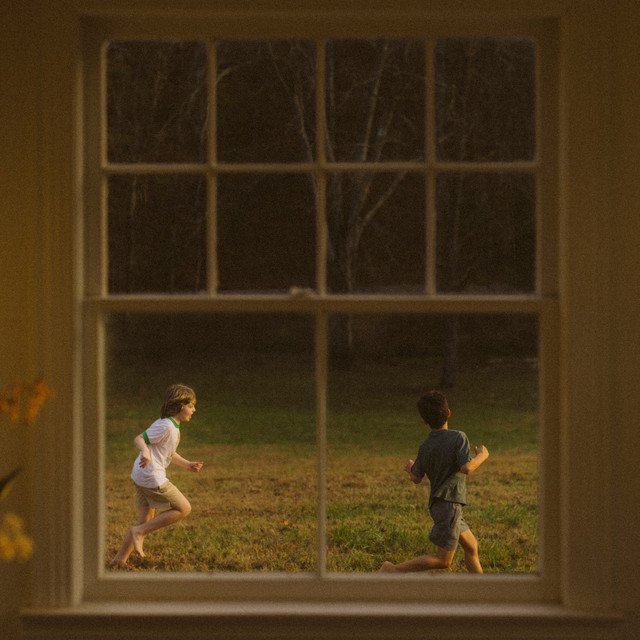

The Video

Directed by Parker Schmidt, the video follows two children, younger versions of Kahan and the friend the song is for, through a friendship that unravels somewhere between adolescence and adulthood.

Warm Vermont light, recurring shots of the two running either toward or away from each other depending on the moment in the song.

There are Easter eggs for those who want them, the phone number from “She Calls Me Back,” the gas station price that mirrors the album’s release date, but the image that lingers is simpler.

Orange juice appears twice. He offers it to his friend. His friend doesn’t take it. Kahan left that in the cut.

One shot near the end shows a sun visor with a “Call Your Mom” sticker and a Polaroid of the album cover tucked beside it. The video doesn’t reinterpret the song. It records it from another angle.

The Album

The Great Divide is Kahan’s fourth studio album. Written across Nashville, a pond in Guilford, Vermont, a studio in upstate New York, and a farm with a firetower in Only, Tennessee, it has been framed by Kahan himself as an attempt to confront the people and places he’s carried quietly for years.

The title track sits at position six on the album. Not the opener. Not the closer. Whatever weight the surrounding songs carry, this is what they’re building toward or away from.

“The Great Divide” doesn’t give Kahan a way out. There’s no accounting for youth, no tidy explanation that makes silence understandable. He was there. He watched.

The song runs five minutes partly because the instrumental close needs somewhere to go after the lyric runs out of road, and partly because that kind of guilt doesn’t compress well. It needs the full stretch. It needs to exhaust itself without quite arriving anywhere.

That’s what the Fenway crowd was already screaming back at him in 2024.

Not the melody.

The admission.

The Great Divide is out April 24, 2026 on Mercury/Republic.

You might also like:

- Orange Juice by Noah Kahan: The Full Story Behind the Fan-Favourite Track

- Unpacking the Powerful Lyrics and Meaning of Noah Kahan’s Stick Season

- Sam Fender ‘People Watching’ Lyrics: A Deep Dive Into His Most Personal Track Yet

- Sam Fender & Olivia Dean’s Rein Me In: Harmonies of Regret and Release

- Boygenius’ Cool About It: A Deep Dive into the Lyrics, Meaning, and Video

- A Night of Redemption: Unveiling the Meaning Behind Zach Bryan’s Revival Lyrics